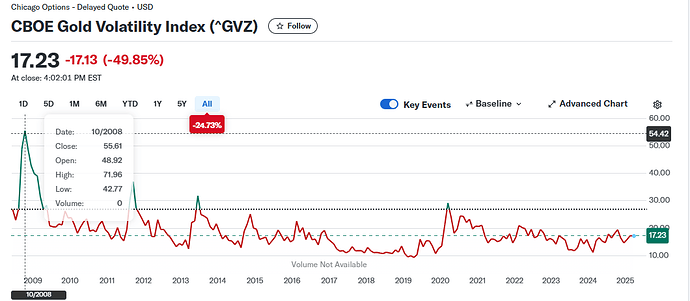

Based on the 2008 volatility calculation, there is a profit‑loss ratio of 3–4 times.

The win rate over 4–10 years is subjectively estimated to exceed 90%.

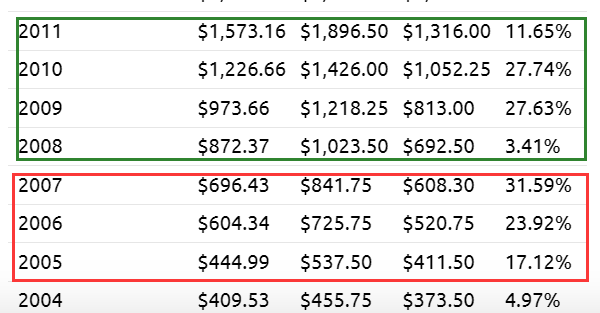

Currently COMEX gold price is fluctuating around $2,900 per troy ounce

Excluding the gains since 2023, it is expected that over the long term (more than 4 years) there is still about 90% upside potential ($5,500 per troy ounce)

If you don’t want to earn the last copper coin, you can start gradually liquidating when it gets close to 4,800 points

I, as a junior, have one thing I don’t understand: why can volatility be used to derive the profit‑loss ratio?

Rough Estimate Based on the 2008 Crisis

Long-term volatility assumed at 25%

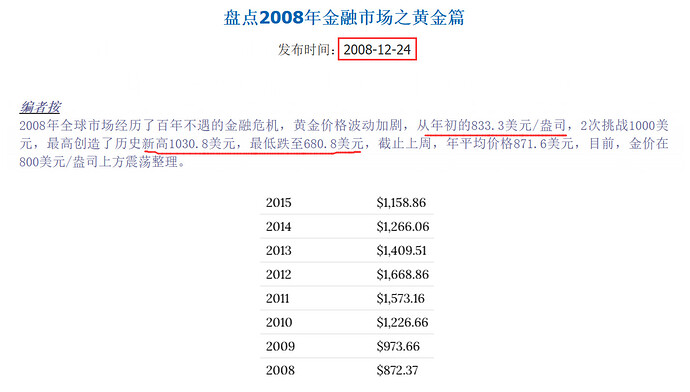

Around 2008 (2005‑2011) the increase was close to 255%

This time it has already risen 50%, with a potential gain of 136%

(1+136%)/(1-25%) = 3.15

The Actual Profit‑Loss Ratio May Be Higher

Ray Dal

This part is wrong

Excluding the current 50% profit, the potential profit is 156%

(1+156%)/(1-25%)=3.41

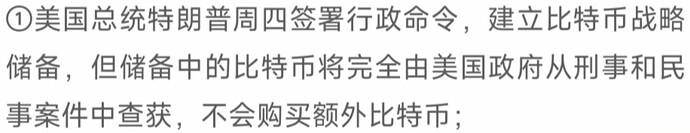

Could Bitcoin possibly rise to 200k?

In March, Dalio warned of the possibility that the U.S. government could ban bitcoin as it did with gold during the 1930s if the cryptocurrency is seen as a competitive threat to Treasury bonds.

However, James Ledbetter, editor of fintech newsletter FIN and a CNBC contributor, previously told CNBC Make It that it’d be quite difficult for the government to effectively ban bitcoin.

Ray’s BTC holdings are less than his gold holdings, so the risk of government regulation must be considered (Trump says he supports BTC but how he will actually act is hard to predict)

| Date | Event Description |

|---|---|

| 1933 | U.S. Executive Order No. 6102 prohibited citizens from owning and trading gold (excluding jewelers and gold coin collectors). |

| January 30, 1934 | The U.S. Gold Reserve Act required the Federal Reserve to turn over all gold to the Treasury, and private gold was sold to the Treasury at a low price of $35 per ounce. For the next 38 years, the gold price was fixed at $35 per ounce. |

| April 24, 1964 | The United States relaxed the gold ban, allowing individual investors to own gold. |

| March 17, 1968 | The “Gold Pool” was dissolved. |

| August 15, 1971 | U.S. President Nixon announced the closure of the gold window, suspending foreign governments or central banks from exchanging dollars for gold. |

Impressive excerpts:

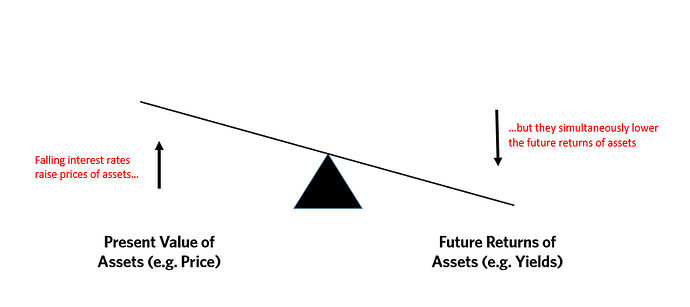

$13T of funds are idle in these zero‑return assets, and the Fed is almost unable to raise rates (the Fed itself is the largest creditor and cannot tolerate falling asset prices)

Right now, approximately 13 trillion dollars’worth of investors’money is held in zero or below-zero interest-rate-earning debt. That means that these investments are worthless for producing income (unless they are funded by liabilities that have even more negative interest rates). So these investments can at best be considered safe places to hold principal until they’re not safe because they offer terrible real returns (which is probable) or because rates rise and their prices go down (which we doubt central bankers will allow).

Most investors are seeking the present value effect from falling rates, rather than actual investment returns

And currently the short‑ and long‑term yield curve is almost flat, and real rates have turned negative

Thus far, investors have been happy about the rate/return decline because investors pay more attention to the price gains that result from falling interest rates than the falling future rates of return. The diagram below helps demonstrate that. When interest rates go down (right side of the diagram), that causes the present value of assets to rise (left side of the diagram), which gives the illusion that investments are providing good returns, when in reality the returns are just future returns being pulled forward by the“present value effect.”As a result future returns will be lower.

That will end when interest rates reach their lower limits (slightly below 0%), when the prospective returns for risky assets are pushed down to near the expected return for cash, and when the demand for money to pay for debt, pension, and healthcare liabilities increases. While there is still a little room left for stimulation to produce a bit more of this present value effect and a bit more of shrinking risk premiums, there’s not much.

Different investors are bullish on different assets, leading to a situation where all assets appear bullish, yet the Treasury yield curve spread and real rates do not lie

Most people now believe the best“risky investments”will continue to be equity and equity-like investments, such as leveraged private equity, leveraged real estate, and venture capital, and this is especially true when central banks are reflating. As a result, the world is leveraged long, holding assets that have low real and nominal expected returns that are also providing historically low returns relative to cash returns (because of the enormous amount of money that has been pumped into the hands of investors by central banks and because of other economic forces that are making companies flush with cash). I think these are unlikely to be good real returning investments and that those that will most likely do best will be those that do well when the value of money is being depreciated and domestic and international conflicts are significant, such as gold. Additionally, for reasons I will explain in the near future, most investors are underweighted in such assets, meaning that if they just wanted to have a better balanced portfolio to reduce risk, they would have more of this sort of asset.

Cyber Fight the Landlord.

Ray’s new article “The Effects of Tariffs: How the Machine Works” AI translation draft:

Tariffs are a type of tax with the following characteristics:

- Generate revenue for the imposing country: foreign producers and domestic consumers share the tax burden (the exact distribution depends on the relative elasticities of the two sides), making tariffs an attractive form of taxation.

- Reduce global production efficiency: tariffs weaken production efficiency worldwide.

- Create stagflation effects on the global economy: they are more deflationary for taxed producers, but more inflationary for the importing country imposing the tariffs.

- Protect domestic firms from foreign competition: in the domestic market of the importing/taxing country, tariffs provide greater protection to local firms. Although this may reduce their efficiency, if overall domestic demand is maintained through monetary and fiscal policy, these firms will have greater survivability.

- Essential during major power international conflicts: tariffs can ensure domestic production capacity to cope with potential international conflicts.

- Reduce current and capital account imbalances: simply put, this means decreasing reliance on foreign production and foreign capital, which is especially important during global geopolitical conflicts or wars.

The above are the first-order effects of tariffs.

What happens next largely depends on the following factors:

- How the taxed country responds to the tariffs;

- How exchange rates change;

- How central banks in each country adjust monetary policy and interest rates;

- How national governments address these pressures through fiscal policy.

These are second-order effects.

More specifically:

- If tariffs trigger reciprocal retaliatory tariffs, the result will be a broader stagflation effect;

- If monetary policy is loose, real interest rates fall, and the currency of the country facing the greatest deflationary pressure depreciates (the normal central‑bank response); or if monetary policy tightens, real interest rates rise, and the currency of the country facing the greatest inflationary pressure appreciates (also a normal central‑bank response);

- Loosening fiscal policy where deflationary weakness appears, or tightening fiscal policy where inflationary pressure appears; such adjustments can partially offset deflation or inflation impacts.

Thus, many “dynamic variables” affect tariff market outcomes and must be carefully weighed. These influences are not limited to the six first‑order effects mentioned earlier; they are also affected by second‑order effects.

However, from a background and future perspective, the following points are clear:

- Production, trade, and capital imbalances (especially debt) must decline in some manner: because they are dangerous and unsustainable on monetary, economic, and geopolitical levels (hence the current monetary, economic, and geopolitical order must change).

- They may be accompanied by sudden and unconventional changes (as described in my new book “How Nations Go Broke: The Big Cycle”).

- Long‑term monetary, political, and geopolitical impacts will primarily depend on:

- The trustworthiness of debt and capital markets as stores of wealth;

- The productivity levels of each country;

- The political systems that make a country an ideal place to live, work, and invest.

In addition, there is much discussion currently about the following two points:

- Whether the U.S. dollar’s status as the world’s primary reserve currency is beneficial;

- Whether a stronger dollar is advantageous.

Obviously, the dollar’s role as a reserve currency is a good thing (because it creates greater demand for U.S. debt and other capital, which would not exist without this privilege). However, because markets drive these phenomena, it inevitably leads to privilege abuse, over‑borrowing, and debt problems, resulting in the situation we now face (i.e., the inevitable reduction of imbalances in goods, services, and capital, the need for extraordinary measures to ease debt burdens, and a reduced external dependence due to geopolitical conditions).

More specifically, some have suggested that the renminbi should appreciate, which could be part of a trade and capital agreement between China and the United States, ideally reached during a leaders’ summit. Such an adjustment and/or other non‑market, non‑economic interventions would generate unique and complex shocks to the involved countries, thereby triggering some of the second‑order effects I mentioned earlier to cushion these impacts.

I will continue to monitor future developments and promptly report to you the first‑ and second‑order effects I believe may arise.

How Countries Go Broke: The Overall Big Cycle

If I had to pick the most important chapter in the book, it would be this one. It discusses the largest and most important forces that are dramatically reshaping the world order, and shows how and why those forces repeatedly drive history through the cycles of a big cycle. After witnessing so many cycles, observing what is happening now feels like watching a movie I’ve seen many times—only this is a modern version, with characters dressed in more contemporary clothes and using more advanced technology. I want to show you what I see. By showing what happened in the past and why, we can understand why developments that were once unimaginable are now occurring, and may happen again in the future.

Although the book mainly focuses on understanding the dynamics of debt/credit/money/economic cycles, we cannot look at those dynamics in isolation, because the occurrence of those cycles is affected by other major forces. Likewise, to understand what is happening in other areas, we need to understand the forces of debt/credit/money/economics, because they have a huge impact on the development of most fields. These five major forces together create the overall big cycle that leads to fundamental changes in monetary, domestic, and/or world order.

I explain in detail in Principles for Dealing with a Changing World Order how this overall big cycle works and how it has manifested over the past 500 years, but I’m not going to cram that 600‑page book into this section. Instead, I’ll give you a short summary. That way, when we move to Part 3, which describes what is happening in our current big cycle, and Part 4, where I try to look ahead, you’ll be able to see how the actual events compare with my debt‑cycle and overall‑big‑cycle template.

How the Machine Works

Because everything that happens has a cause behind it, to me everything is changing like a perpetual motion machine. To understand this machine you need to understand its mechanical principles. Since everything influences everything else directly or indirectly, those mechanical principles are very complex. Sometimes I’ll explain in great detail what I know to illustrate the complexity, as I did earlier when I explained how countries go broke. Other times I’ll keep it simple. As the saying goes, “Any fool can make something complicated. It takes a genius to make it simple.” In this chapter I’ll try to explain the big cycle simply. I’ll start by explaining my approach.

As a global macro investor for most of my career, I have tried to understand and model causality and use my models to forecast what markets will do. To that end, over roughly the past 35 years I built a computerized expert system that lets a computer make decisions the way I do. Those systems are based on the principle that decision systems should be built on timeless and universal relationships—that is, they should be able to explain major developments across all time frames and all countries, even if not with perfect precision or detail. If they cannot explain major developments across all time frames and countries, that signals a missing important factor that needs to be added to the template/model.

The expert system I built is an early form of artificial intelligence. Now, with the many breakthroughs in AI, I believe we are on the cusp of being able to understand the causal relationships that drive everything, even though we still have to rely on the old way—people using today’s computing and AI tools to study what is happening. That is why, to try to understand and describe the most important mechanisms that are changing the world as we know it, I conducted deep research and created explanations for them. What follows is the result of that process. Because the forces that drive the big cycle are so massive, we can see and understand them without getting bogged down in details and complexity.

From the highest level, the five most important change drivers are:

- Debt/Credit/Money/Economic Cycle

- Internal Order and Disorder Cycle

- External Geopolitical Order and Disorder Cycle (i.e., the changing world order)

- Natural Disasters (droughts, floods, pandemics)

- Human creativity, especially the invention of new technologies

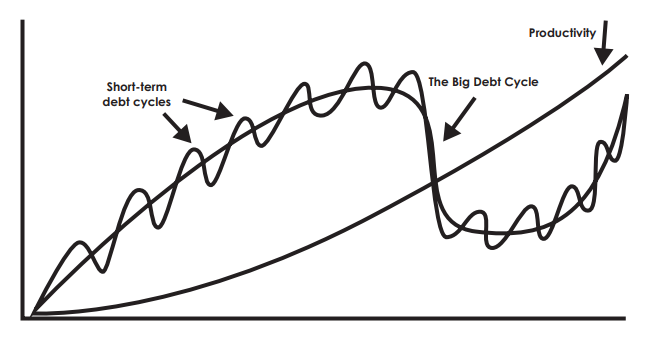

These forces interact, shaping the biggest events and forming a cycle that oscillates around an upward‑sloping trend line. The upward slope of that trend line is mainly driven by the creativity of actual people (e.g., entrepreneurs) who have ample resources (such as capital) and cooperate well with others (colleagues, government officials, lawyers, etc.) to create productivity‑enhancing inventions and products.

In the short term (1‑10 years), short‑term cycles—especially debt and political cycles—dominate. In the long term (10 years plus), long‑term cycles and the upward‑sloping productivity trend line have a larger impact.

As I explained earlier, conceptually this dynamic looks like this:

I will now dive into those five forces. As you read about them, think about how they work and how they are operating now. That will help you see “how history rhymes,” better understand what is happening now, and anticipate what might happen.

How the Overall Big Cycle Works: The Five Major Forces

We are now in the 80th year of the big cycle that began after World II. The cycle is unfolding in a classic way that will produce massive changes that can only be imagined by visualizing those five forces interacting together in a historical context.

Specifically:

1. Debt/Credit/Money/Economic Cycle

In this book I have already described the most important factors that affect the big debt cycle (such as debt‑service payments relative to income, the amount of newly issued debt relative to demand, the willingness of debt‑asset holders to hold existing debt assets, and other factors previously explained).

Because I have covered this big debt cycle so comprehensively, I won’t repeat it here. In short, the cycle is:

- Debt‑service ratio – how much of income must go to paying interest and principal.

- New‑debt issuance vs. demand – how much fresh borrowing is created when demand is high or low.

- Holder willingness – how willing creditors are to keep existing debt on their books.

If you follow the template, you will see that the debt cycle is a long‑term (decades‑long) upward‑sloping trend line punctuated by short‑term (year‑to‑year) oscillations.

2. Internal Order and Disorder Cycle

How countries relate to each other is crucial, and that relationship is also cyclical.

Because there are periods of order (harmony, productivity, prosperity) and disorder (major conflict, destruction, depression) domestically, the same pattern appears internationally: there are periods of order (harmony, productivity, prosperity) and periods of disorder (major conflict, destruction, depression). Disorder periods arise when nations fight over who gets to set what order.

Because there has never been an effective global governance system, world order is more prone to slip into disorder and conflict.

As part of the big cycle, there are also large swings between unilateralism and multilateralism. Unilateralism pursues self‑interest, the strong dominate the weak, jungle law / survival of the fittest. Multilateralism seeks global harmony, peaceful coexistence, and equality.

Historically, multilateralism only takes hold after wars, when people are tired of fighting and a dominant power can enforce how things should be done. In most historical periods, harsh, destructive unilateralism is the norm, while multilateralism—pursuing harmony, peaceful coexistence, and common interests—is extremely rare and never sustained. For example, it was not until the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, after the devastating Thirty Years’ War, that European states agreed on borders and pledged to respect them, rather than constantly battling each other for territory—a pattern that had been the norm before.

Another example: after World I, idealist Princeton president Woodrow Wilson became U.S. president in 1913 and naïvely expected a world‑governance system modeled on the American system—the League of Nations. It failed to prevent World II, after which a new U.S.–led world order emerged, creating the United Nations, IMF, World Bank, WHO, WTO, International Court of Justice, WIPO, and other multilateral institutions. The United States, with its unparalleled economic and military strength, became the pillar of that liberal international order, promoting democracy, free markets, and human rights. Although imperfect, that system has so far prevented another world war.

We have all experienced a period when multilateralism—pursuing harmony, peaceful coexistence, and equality—was desirable, but now multilateralism is fading and unilateralism is rising, a shift that makes sense in historical context. As a result, the power of multilateral organizations is rapidly declining and shifting to great powers. Realists must accept that the desire and existence of global cooperation are receding, the pendulum is swinging toward selfish unilateralism and “survival of the fittest.” Stronger actors bully weaker ones more often. These developments are typical of the current stage of the big cycle.

Although the transition from multilateralism to unilateralism was initially shocking, it quickly becomes normalized. For instance, just a few months before this article was written, Donald Trump’s comments about Greenland, Canada, and the Panama Canal were deemed unimaginable—much like Russia’s use of force to invade Ukraine to protect its interests when those interests cannot be secured peacefully.

In such moments, as the situation changes rapidly, alliances shift quickly, and victory becomes more important than loyalty.

To help us imagine the future, we should pay close attention to historical lessons. Throughout most of history, when borderless societies existed, groups with common interests (tribes) fought each other for wealth—either to seize another tribe’s riches or to protect their own. Winners became richer and more “civilized,” but they also grew more luxurious and weaker, eventually being defeated by stronger “barbarians,” who in turn were later overcome by even stronger descendants. This pattern repeats in the rise and fall of empires—from Rome’s ascent and defeat by the Gauls to the cycles of most dynasties and the accompanying swings in leadership styles. Those alternating barbarian and civilized eras create periods where, when the “civilized” side is weak and the “barbarian” side is strong, the more advanced civilization is destroyed.

History repeatedly shows that excessive civilization leads to soft decay, ultimately losing to strong barbarism.A peaceful and productive modern version is the “struggle” that occurs in the business world, driven by inventing new effective business ideas/weapons to promote creative destruction. We enjoy watching these struggles, much like watching battles in the Roman Colosseum, or even better, we enjoy participating in them. Frankly, I like to be involved; I despise unrealistic idealism (though I favor pragmatic idealism the most). However, this impulsive, destructive version leads to a lack of cooperation and fuels battles in politics, geopolitics, responses to natural disasters (especially climate change), and new technologies, which worries me greatly.

4. Natural Disasters (Droughts, Floods, and Pandemics)

Throughout history, natural disasters have killed more people than wars and have disrupted order more than any of the forces mentioned earlier. An objective look at the data shows that droughts, floods, and pandemics are increasing and becoming more costly. While the reasons for this trend remain debated, there is no dispute that it is happening. It is also undeniable that human pollution and environmental degradation, rising population density, tighter global connectivity (due to increased international travel), and closer contact with other species through land development (leading to animal‑human disease transmission) are all contributing factors. We see these situations frequently in the news; a recent example is the wildfires in Los Angeles. It is almost certain that these problems will worsen.

Like the other forces, this one intertwines with the major forces shaping what is happening. For example, immigration pressures in developed countries (driven by climate change) and living‑condition challenges in developing nations (as people strive to adapt to droughts, floods, and other changes) are clearly exacerbated by the rise in natural disasters. Given that virtually every country faces debt issues and lacks sufficient funds for climate mitigation or adaptation, the situation is dire.

5. Human Creativity, Especially the Invention of New Technologies

Technology has made tremendous strides, especially in the field of artificial intelligence, which will have profound effects on thinking across all domains, for better or worse.

Historically, technological progress has raised living standards and life expectancy, generated economic and military power, and caused massive destruction in wars. It is closely linked to the other four forces. When technological advancement is supported by sound financial, economic, and social conditions, it progresses faster than when those conditions are poor. However, if its development is fueled by unsustainable credit growth, it often triggers financial bubbles and crashes. Examples include the South Sea Bubble during the Dutch Empire’s decline in 1720, the railway mania of the 1830s‑1840s, the electricity and utilities bubbles of the 1870s‑1890s (“War of the Currents”), and the internet bubble and telecom collapse of 1990‑2001. These illustrate how major technological improvements that boost living standards and productivity can also lead to debt bubbles, crashes, and massive transformative change.

That concludes the discussion of the great cycles—enough to help you better understand the dynamics of the events in our current great cycle since the end of World II in 1945, as covered in Part III. This will also aid you in grasping the perspective I attempt to project for the future in Part IV. Before proceeding, it is worth sharing a final principle that has the greatest impact on handling the challenges that arise within great cycles:

The greatest and most important force is how people treat one another.

If people solve problems and seize opportunities together rather than fighting each other, they can achieve the best outcomes. Unfortunately, despite the many advances in technology, human nature has changed little, so this may still lie beyond humanity’s capacity.

China also retaliated with tariffs

Summary: The United States is about to face greater inflation, and China is about to face greater deflation

USD/CNY: Ray Dalio Sees US, China Push for Yuan Deal as Part of Trade Relief - Bloomberg

Bridgewater Associates founder Ray Dalio (Ray Dalio) recently said after meeting with senior Chinese officials that the United States and China could reach an agreement to strengthen the renminbi exchange rate in order to obtain tariff reductions.

Dalio posted on social media X on Friday, writing: “I can imagine that the US and China might engage in negotiations where the renminbi appreciates relative to the dollar in exchange for some trade relief.”

Dalio added: “If this were to happen, it would be more deflationary for China and would bring economic downside pressure, so China might need to implement more accommodative monetary and/or fiscal policies.”

Before making these remarks, Dalio had met with several senior Chinese officials, including Vice Premier He Lifeng, People’s Bank of China Governor Pan Gongsheng, and Commerce Minister Wang Wentao.

On Friday, China announced a 34% tariff on all goods imported from the United States, matching the level of the so‑called “reciprocal” tariffs the U.S. imposed on Chinese products earlier this week. Then‑President Donald Trump sharply criticized China’s retaliatory measures and vowed that his economic policy “will never change.”

This week, the renminbi exchange rate has been relatively stable, after the People’s Bank of China supported it by setting a daily midpoint stronger than market expectations.

Chinese officials have historically been cautious about excessive renminbi appreciation. They point to the appreciation of the yen after the 1980s Plaza Accord, which they say contributed to Japan’s so‑called “lost decade.”

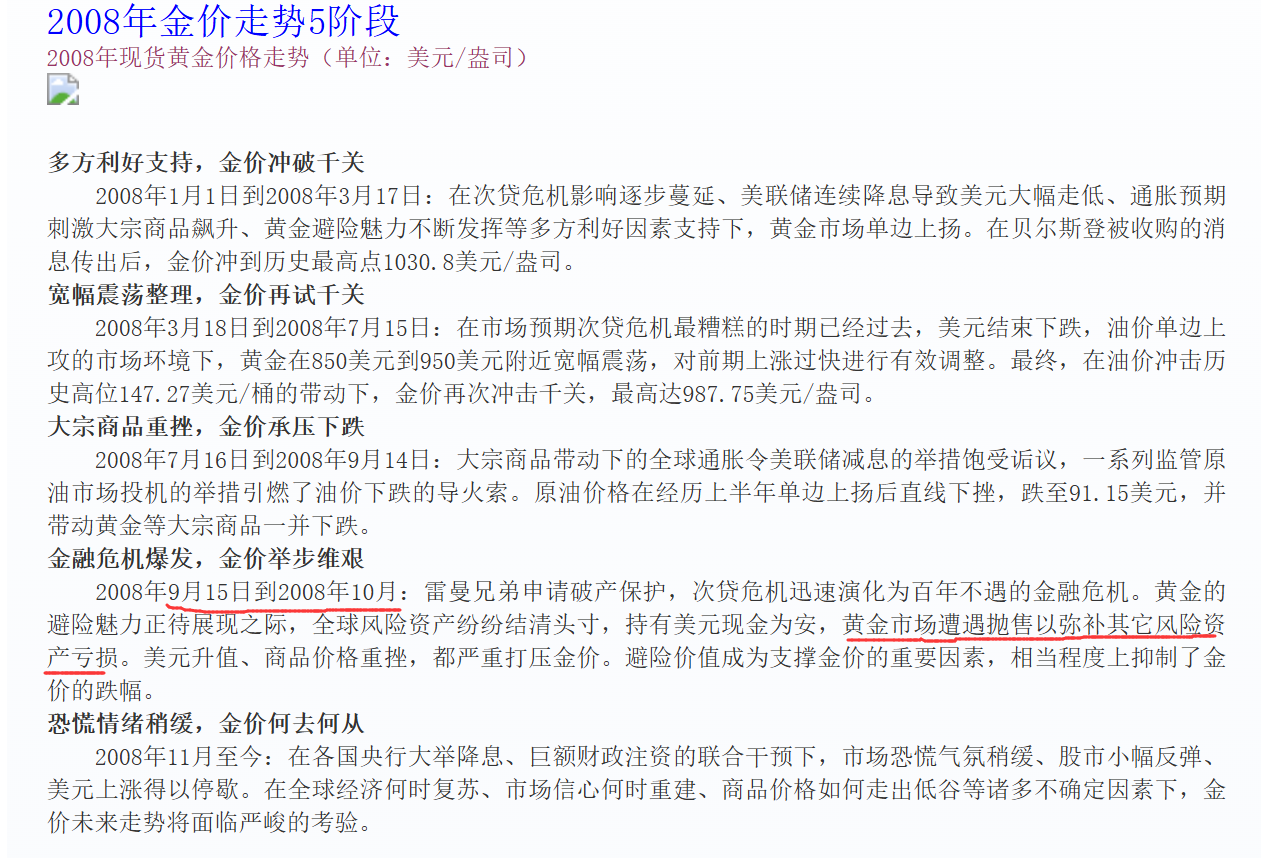

An old news item from 2008

During periods when various global assets decline, many entities get liquidated, forcing them to sell gold to meet margin calls; gold can also see a sharp short‑term correction

Because it is a 2008 news piece titled “Future trend faces severe test,” we now know the result of that test

From the beginning of the year to now gold has risen 20%; after the tariff policy was implemented, global assets indeed fell, and gold fell along with them, but (1) the decline is still limited (2) central banks in various countries have stepped in, so the gold price over the next 12 months is completely unpredictable; volatility will not be low, so it is recommended to wait for opportunities and add positions in small batches.

Gold has been reportedly been used to meet the largest margin calls since Covid 2020 from hedge funds this week, per Standard Chartered.

According to Standard Chartered, hedge funds used gold this week to meet the largest margin calls since the COVID‑19 pandemic in 2020.

History rhymes once again

Ray’s new article:

“Don’t Mistake the Current Events as Primarily Caused by Tariffs”

At this moment, people naturally focus heavily on the announced tariffs and their massive impact on markets and the economy, while paying little attention to the underlying causes and the potentially looming major upheavals.

Don’t get me wrong: although these tariff announcements are very important developments—and we all know they were triggered by President Trump—most people overlook the fundamental reasons that got him elected and led to these tariffs. They also largely ignore the more important forces that drive almost everything (including tariffs).

It must be remembered that we are witnessing a classic, large‑scale collapse of the monetary, political, and geopolitical order. Such a collapse happens roughly once in a lifetime, but historically it has occurred many times whenever similarly unsustainable conditions have arisen.

More specifically:

The monetary/economic order is collapsing because existing debt is too large, growing too fast, and the current capital markets and economy depend on this unsustainable massive debt. The debt is unsustainable because

a) Debtors – borrowers owe too much and, addicted to financing their over‑consumption through debt (e.g., the United States), continue to borrow excessively;

b) Creditors – lenders (e.g., China) hold too much debt and rely on selling goods to the borrowing countries (e.g., the United States) to sustain their economies. These imbalances face huge corrective pressures, and the way they are corrected will fundamentally reshape the monetary order.

For example, in a de‑globalized world, having both large trade imbalances and large capital imbalances is clearly contradictory; the major participants cannot trust that others will not cut off the supply of needed goods (the U.S. concern) or refuse to pay what they owe (the Chinese concern). This is because each side is effectively in a state of war, making self‑sufficiency vital.

Anyone who has studied history knows that, under such conditions, these risks repeatedly produce the kinds of problems we see today. Consequently, the old monetary/economic order—where countries like China produce cheaply, sell to the United States, and acquire U.S. debt assets, while Americans borrow from China to buy those products and accumulate massive debt—must change. These obviously unsustainable arrangements are worsened by the decline of U.S. manufacturing, which not only hollowed out middle‑class jobs but also forces the United States to import needed goods from a nation increasingly viewed as an adversary. In a de‑globalized era, the large trade and capital imbalances reflect the inter‑linkage of trade and capital and must be reduced in some way. At the same time, it is evident that the U.S. government’s debt level and the rate at which it is rising are unsustainable. (You can find my analysis of this issue in my new book How Nations Go Bankrupt: The Big Cycle.) Clearly, the monetary order will have to be altered in a large‑scale, disruptive manner to reduce all these imbalances and excesses, and we are in the early stages of that process. This has huge economic implications for capital markets, which I will explore in depth at another time.

The domestic political order is collapsing because there are huge gaps among people’s education, opportunity, productivity, income, wealth, and values—and because the existing political system cannot effectively address these gaps.

These conditions manifest in the all‑out battles between right‑wing populists and left‑wing populists, each seeking power and control to run affairs. This leads to the breakdown of democratic institutions, because democracy requires compromise and the rule of law, both of which history shows tend to collapse in periods like the one we are now experiencing. History also shows that when classic democracy and the rule of law are removed as obstacles to authoritarian rule, powerful autocratic leaders emerge. Clearly, the current unstable political climate will be influenced by the other four forces I mentioned—e.g., problems in the stock market and the economy can spark political and geopolitical issues.

The international geopolitical world order is collapsing because the era in which a single dominant country (the United States) set the rules for others has ended. The U.S.–led multilateral cooperative order is being replaced by unilateral, power‑based rule‑making. In this new order, the United States remains the world’s largest power but is shifting toward a unilateral “America First” approach. We now see this in U.S.–led trade wars, geopolitical confrontations, technology battles, and, in some cases, military conflicts.

Natural phenomena (droughts, floods, pandemics) are becoming increasingly destructive,

and astonishing technological changes such as artificial intelligence will have major impacts on every aspect of life, including the monetary/debt/economic order, the political order, the international order (by affecting economic and military interactions between nations), and the costs of natural events.

We should pay attention to how these forces change and interact with each other.

Therefore, I urge you not to let headline‑grabbing events like tariffs distract you from the five major forces and their interrelationships, which are the true drivers of the overall long‑term cycle. If you allow yourself to be sidetracked by these surface phenomena, you will

a) overlook how the conditions and dynamics of these large trends generate the headline‑making events;

b) be unable to think through how those headline events will affect the underlying trends; and

c) fail to focus on understanding how the overall long‑term cycle and its components usually unfold, which would tell you a great deal about what may happen in the future.

I also encourage you to contemplate these crucial interrelationships. For example, consider how Donald Trump’s tariff actions will affect

- the monetary/market/economic order (they will damage that order);

- the domestic political order (they may damage it by eroding his support base);

- the international geopolitical order (they will cause financial, economic, political, and geopolitical damage in many obvious ways);

- the climate (they will, to some extent, weaken the world’s ability to effectively address climate change); and

- technological development (they will harm the U.S. in some positive ways, such as bringing more tech production onto American soil, but also in harmful ways, such as disrupting capital markets that support tech development, among countless other effects).

When you conduct this thinking, it helps to remember that what is happening now is just a contemporary version of events that have occurred countless times throughout history. I urge you to study how policymakers acted in similar historical cases, where they found themselves in comparable positions, to help you list what they might do—for example, suspending debt‑service payments to hostile nations, imposing capital controls to prevent capital flight, or levying special taxes. Many of these actions were unimaginable not long ago, so we should examine their effects. The collapse of the monetary, political, and geopolitical orders manifests as economic depressions, civil wars, and world wars, which then give rise to new monetary and political orders that manage internal interactions and new geopolitical orders that manage interstate interactions—until they collapse again, in a repeating cycle. I describe these processes in detail in my book Principles for Navigating a Changing World Order, where you can see their layout clearly. The overall long‑term cycle is divided into six identifiable phases, each unfolded sequentially. The book details each phase, making it easy to compare what is happening now with typical patterns, thereby identifying the cycle’s current stage and what may follow.

When I wrote that book and others, I hoped—just as I still hope—to achieve three goals:

- Help policymakers understand these forces and interact with them to craft better policies and obtain better outcomes;

- Help individuals who can influence policy collectively—not just individually—navigate these forces to achieve better results for themselves and those they care about;

- Encourage smart people with differing views to engage with me in open, thoughtful dialogue so we can all work toward uncovering the truth and figuring out how to respond.

The views expressed here are my personal views and do not necessarily represent the views of Bridgewater Associates.

Ray:

Now is an excellent time for all stakeholders to reconsider their approaches! When dealing with unsustainable debt and imbalances, there are better and worse ways. President Trump decided to abandon a worse approach and address these imbalances through negotiation, which is a better way. I hope and expect he will take the same approach toward China; I believe this includes negotiating an agreement that would appreciate the renminbi against the dollar, specifically by China selling dollar assets while loosening fiscal and monetary policy to stimulate domestic demand. This would be a win‑win outcome. China should also restructure and monetize its excessive local‑government debt to shed the debt burden. In any case, the debt/monetary order must undergo a major change to resolve debt, trade, and capital imbalances. The next step for the Trump administration should be to reduce the deficit to 3% of GDP, properly addressing the deficit issue. I describe in detail how to achieve this without causing chaos in How Nations Go Bankrupt: The Big Cycle; you can read the relevant content at the following link: How Countries Go Broke: Chapter 15 & Chapter 16.

For investors who are shocked and fearful because of recent events (and possible future ones), this is also an excellent time to reassess their portfolio structure to avoid taking on intolerable risk. I can guarantee that sooner or later another market‑panicking event will occur.

While I cannot explain in detail here how to construct a portfolio, I can recommend that interested parties take the “Dalio Market Principles” course developed by the Wealth Management Institute (WMI), founded by the Singapore government, which aims to help investors raise their knowledge level: https://wmi.edu.sg/dmp-online. Additionally, I am writing my next book Investment and Economic Principles | 投资与经济原则, and I will share parts of it online during the writing process.