Autumn recruitment season has started; I’m writing some canonical computer notes for easy memorization and review

Friends are welcome to supplement, ask questions, or write down the important canonical knowledge you consider essential in the thread

Shallow Copy, Deep Copy, std::move

-

Shallow copy: Copies bytes directly, which solves many scenarios, but when the copied object contains pointers or file descriptors, two kinds of errors can occur:

- During use, the original object and the copy have pointers that refer to the same address; a change in one affects the other, which usually contradicts the intended logic.

- During destruction, both the original and the copy try to destroy the same pointer, leading to a double‑free and undefined behavior.

-

Deep copy: Used to fix the errors described above. A deep copy must be implemented manually (assignment operator / copy constructor). Suppose the original object has a pointer; you allocate a new block of memory and copy the contents pointed to by the original pointer into this new block. Thus the original object and the copy operate independently.

-

std::move: Converts an lvalue to an rvalue, roughly equivalent to

template<typename T>

T&& move(T lvalue) {

return static_cast<T&&>(lvalue);

}

The original code is slightly altered and involves some template syntactic sugar, which is omitted here. Using a = std::move(b); enables move semantics, i.e., transfers ownership of the object. After the move, b returns to a default‑initialized state (the exact state is defined by the move constructor / move assignment operator, as shown below), cannot be used further, but can be safely destroyed.

The following code implements a move constructor and a move assignment operator:

class A{

public:

A() : data(nullptr) {

}

A(int value) : data(new int(value)) {

}

A(A&& other) : data(other.data) {

other.data = nullptr;

}

A& operator=(A&& other) {

if (this != &other) {

delete data;

data = other.data;

other.data = nullptr;

}

return *this;

}

~A() {

delete data;

}

private:

int *data;

};

Lambda Expressions

Usage:

int x= 10;

auto f = [x](int c = 5) {return x + c;};

std::cout << f() << std::endl;

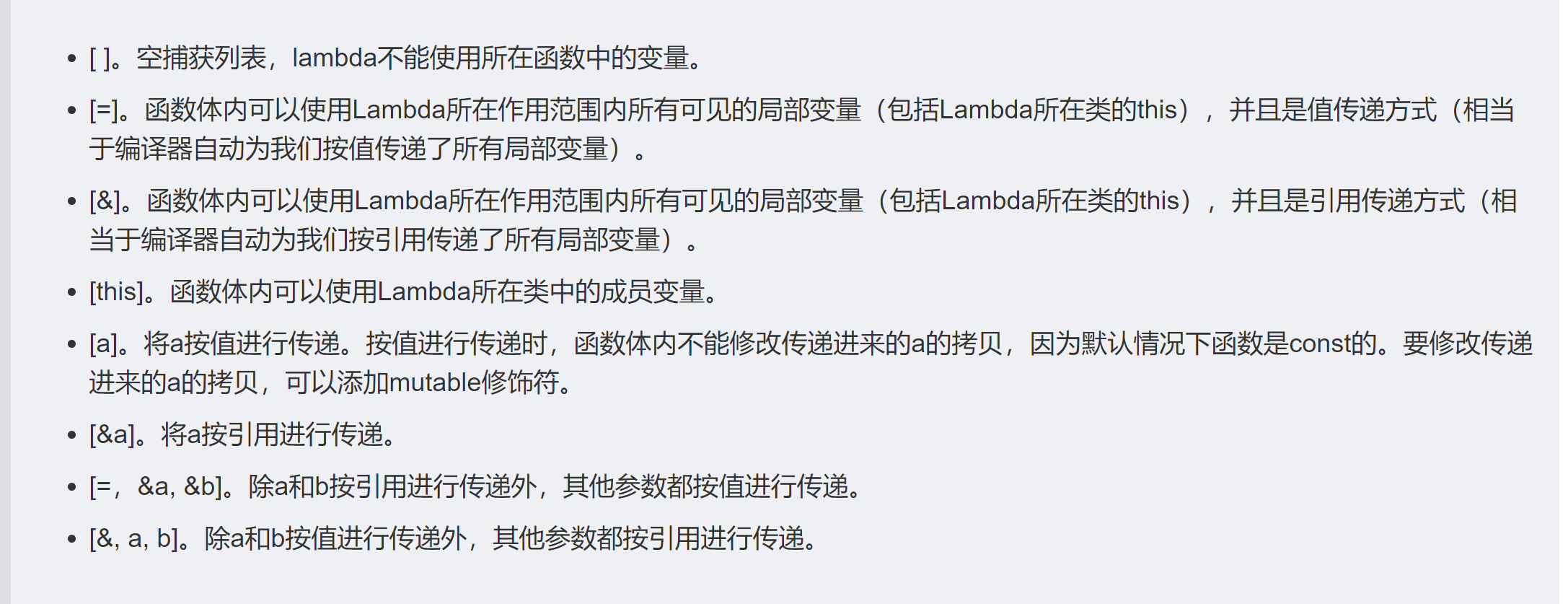

The parameters inside the brackets form the capture list, which can be specified in the following ways:

The parentheses contain the parameter list, used similarly to a function.

To modify the value of x, you need to add the mutable keyword, as shown:

int x= 10;

auto f = [&x](int c = 5) mutable {x=c;};

f();

std::cout << x << std::endl;

Virtual Functions and CRTP Implement Function Polymorphism

Virtual Functions:

class A{

public:

virtual void print() {

puts("A");

}

};

class B: public A{

public:

void print() {

puts("B");

}

};

class C: public A{

public:

void print() {

puts("C");

}

};

int main() {

B x;

A y = static_cast<A>(B);

y.print();

}

Drawbacks:

- Uses an extra vtable pointer in memory compared to CRTP

- At runtime incurs an additional pointer indirection compared to CRTP

- Functions cannot be inlined, causing significant performance impact for short functions

- Code predictability is low, which is detrimental to prefetching and indirect branch prediction

CRTP:

template<typename der>

class A{

public:

void print() {

static_cast<der *>(this)->printName();

}

void printName() {

puts("A");

}

};

class B: public A<B>{

public:

void printName() {

puts("B");

}

};

class C:public A<C>{

public:

void printName() {

puts("C");

}

};

template<typename der>

void CRTP(A<der>& x) {

x.print();

}

int main() {

B x;

CRTP(x);

}

Drawbacks:

- Code logic is more complex, making it harder to read

- Cannot achieve dynamic dispatch

Out-of-Order Execution and Memory Barriers

Out-of-Order Execution:

Many topics were covered in architecture classes (e.g., scoreboard algorithm and Tomasulo algorithm); here’s a pasted excerpt from the web.

Out-of-order processors (Out-of-order processors) typically handle instructions in the following steps:

- Instruction fetch

- Instruction is dispatched to the instruction queue

- Instruction waits in the queue until its input operands become available (once operands are ready, the instruction can leave the queue even if earlier instructions have not executed)

- Instruction is assigned to an appropriate functional unit and executed

- Execution result is placed into a queue (instead of being written to the register file immediately)

- Only after the execution results of all earlier instructions have been written to the register file can the result of this instruction be written (reordering results to make execution appear in order)

From the above process, it can be seen that out-of-order execution avoids waiting for unavailable operands (the second step of in-order execution), thus improving efficiency. On modern machines, the processor runs much faster than memory, and an in-order processor spends much of its time waiting for data that could otherwise be used to process many instructions.

Memory barriers are divided into two categories:

- Compiler barriers

Define variables with thevolatilekeyword;volatilehas three implications:

- The access order between volatile variables will not be altered by the compiler

- Each read of a volatile variable accesses memory

- Volatile variables are not subject to aggressive compiler optimizations

Example:

//thread1

volatile bool tag = true;

volatile int x = 0;

while(tag);

work(x)

//thread2

x = 10;

tag = false;

Here, thread1 enters an infinite loop; thread2 sets x to 10 and writes it to memory, then sets tag to false and writes it to memory. Thread1 reads tag from memory, the loop stops, and work(10) is called.

If volatile is not used, compiler optimizations may cause memory reordering, e.g., in thread2 the assignment x = 10 might be executed after tag = false, potentially causing thread1 to execute work(0).

- CPU barriers

- Ensure ordered reads and writes:

mb()andsmp_mb() - Ensure ordered writes only:

wmb()andsmp_wmb() - Ensure ordered reads only:

rmb()andsmp_rmb()

These memory barriers are used on multi-core processors; compiler barriers alone are insufficient, as cache coherence is also involved, which is beyond the scope of this discussion.

Cache Coherence and Memory Barriers

MESI cache coherence protocol:

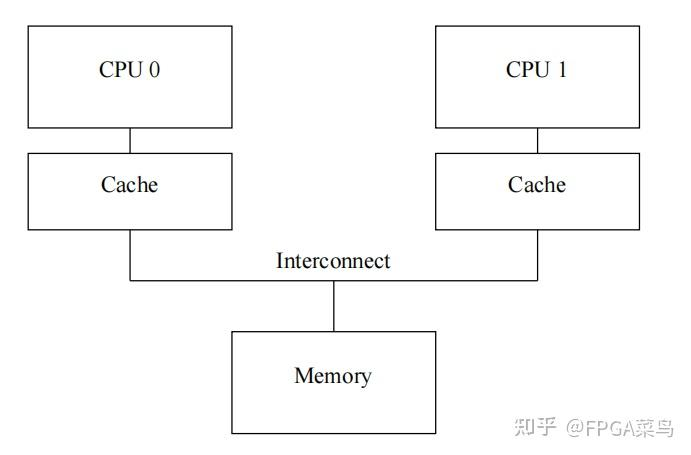

In a dual‑core processor as shown above, memory can be main memory or L3 cache (usually L3 cache).

The two caches refer to L1/L2 caches; for simplicity, assume there is only one level of cache.

Consider the following scenario:

There is a variable x = 0, present in memory and in CPU0’s cache

- CPU1 reads x, cache miss, requests the x data from memory and stores it in its cache

- CPU0 writes x = 1, cache hit, directly modifies it in CPU0’s cache; if the cache is not write‑through, the value of x in memory remains 0

- CPU1 reads x, cache hit, reads x = 0, resulting in an error

To prevent the above situation, the MESI protocol is used to maintain cache coherence.

The MESI protocol has four states, as follows:

I: Invalid – the cache line’s data is invalid.

S: Shared – the cache line is up‑to‑date and at least one other core’s cache also holds that cache line.

M: Modified – the cache line is up‑to‑date and differs from main memory; no other core’s cache holds the latest copy.

E: Exclusive – the cache line is up‑to‑date and matches main memory; no other core’s cache holds a newer copy.

Maintaining these states based on various CPU actions forms a four‑state automaton; during transitions, cores must exchange information.

Possible interaction message types:

Read: Sent on a cache miss, to obtain the latest copy from another core’s cache or from main memory; the message contains the address of the data being read.

Read Response: Response to a Read, containing the latest copy of the requested data.

Invalidate: The receiving cache invalidates the corresponding cache line; the message contains the address to be invalidated.

Invalidate Ack: Acknowledgment of an Invalidate, returned after the cache line has been invalidated.

Read Invalidate: Reads the latest data of a cache line and invalidates the corresponding line in the core’s cache. The message contains the address to be read and invalidated. This signal is typically sent on a write cache miss and requires both a read response and an invalidate acknowledgment.

Writeback: Occurs when a cache line in the M state is evicted, writing the dirty block back to main memory. The message contains the data address and the cache line’s contents.

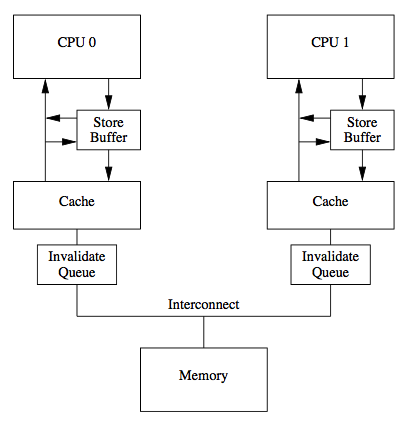

The MESI protocol is correct but not very efficient; however, some simple optimizations can be added, such as Store Buffer and Invalidate Queue

The figure above shows the ARM architecture; the x86 architecture does not have an Invalidate Queue.

Store Buffer

When a CPU experiences a write miss, it must send a Read Invalidate and wait for a response, which can take a considerable amount of time; during this period the CPU cannot do other work, severely impacting performance. A store buffer solves this problem. As shown in the figure, when a write miss occurs, the CPU can send a read‑invalidate signal while storing the data to be written in the store buffer, then continue executing subsequent instructions. Once the other CPU(s) or main memory return the latest data and all invalidate acknowledgments are received, the data is read from the store buffer and written into the cache.

Store Forwarding

Consider the following scenario:

Initially x = 0 and is present in the CPU’s cache.

- The CPU writes x = 1 to the cache; the write is stored in the store buffer and an invalidate operation is issued.

- The CPU reads x; at this point x = 1 is still in the store buffer and has not been committed. Because the cache line hits, it returns x = 0.

Store Forwarding: When the CPU reads data, it first checks whether the data exists in the store buffer; if so, it reads it directly, otherwise it reads from the cache.

Store Buffer and Memory Barriers

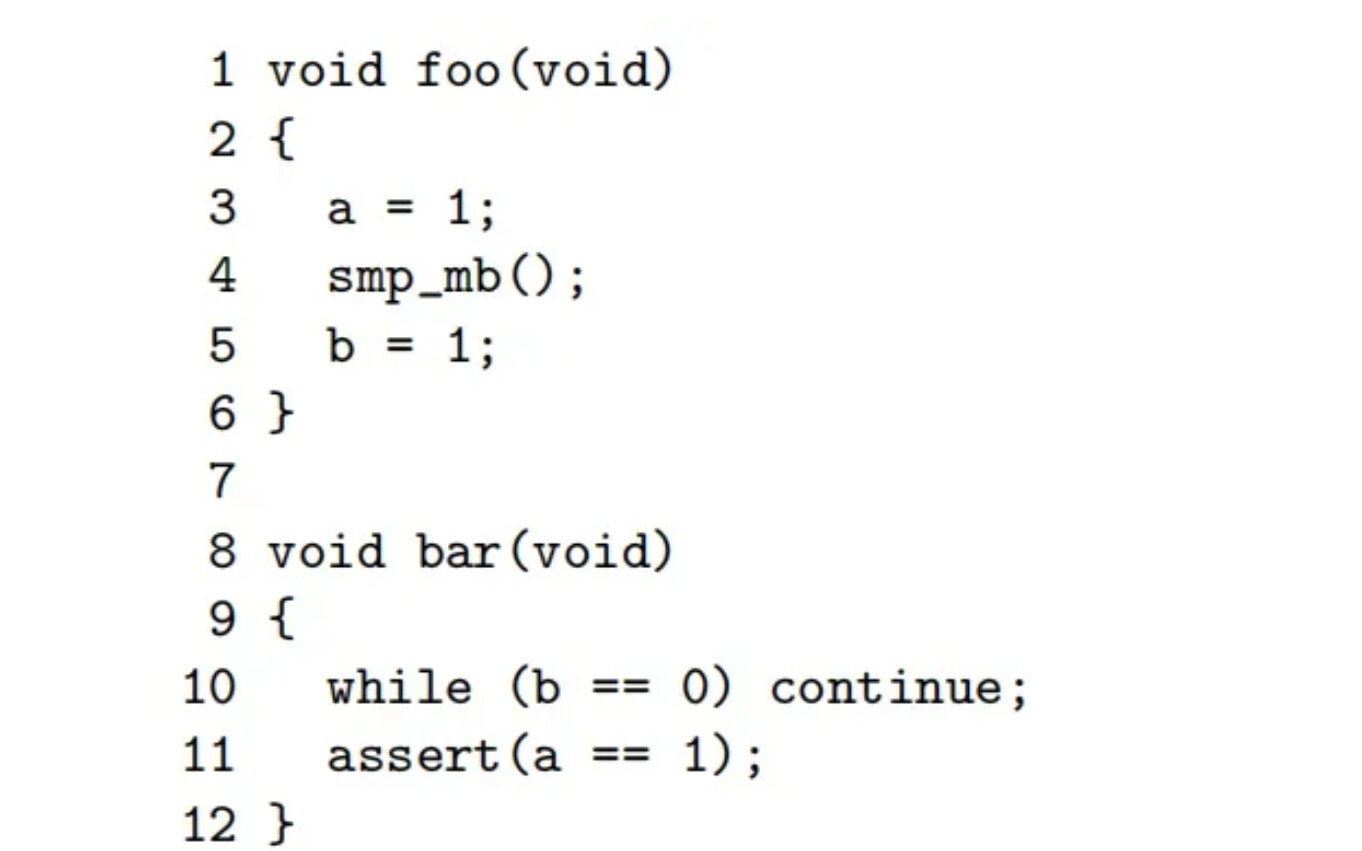

Assume the fourth line smp_mb() is removed from the code above, and consider thread0 executing the foo function on CPU0 while thread1 executes the bar function on CPU1.

Initially, the copy of a resides only in CPU1’s cache and the copy of b only in CPU0’s cache. Consider the following execution order:

- cpu0 executes

a = 1; becauseais not in cpu0’s cache, cpu0 issues a read‑invalidate signal and storesa = 1in the store buffer. - cpu1 executes

while (b == 0). Sincebis not in cpu1’s cache, cpu1 sends a read request for the latest copy ofb. - cpu0 executes

b = 1; becausebis in cpu0’s cache, it hits and simply updates the value to 1. - cpu0 receives the read request from cpu1 and returns the new value of

b(1) to cpu1. - cpu1 receives the new value of

b(1), updates its cache line, and becausebis now 1, exits the while loop. - cpu1 executes

assert(a == 1), discovers thatais still 0, and the assertion fails. - cpu1 receives a read‑invalidate signal, returns the data to cpu0, and invalidates the cache line containing

a. By then it is already too late!

smp_mb() flushes the contents of the Store Buffer to the cache, i.e., it blocks until all stores issued before that point are visible to all CPUs.

Invalidate Queues

A cache’s Store Buffer is usually small; when it becomes full, the CPU must wait for some entry to be flushed before pushing a new store instruction, which can significantly degrade performance. The flush rate of the Store Buffer depends on the response speed of Invalidate Ack messages.

When a CPU receives an Invalidate signal, it does not immediately invalidate; instead it stores all invalidate information in an Invalidate Queue and promptly returns an Invalidate Ack. The Invalidate Queue asynchronously invalidates the cache lines.

Invalidate Queues and Memory Barriers

Consider the following scenario:

CPU1 and CPU2 both hold the latest copy of x = 0 in their caches, with the cache line in the Shared state.

Assume the instructions execute in the following order:

- CPU1 writes

x = 1, sends an Invalidate signal, and places the write into its store buffer. - CPU2 receives the Invalidate signal and returns an Invalidate Ack.

- CPU1’s store buffer receives the Invalidate Ack and writes

x = 1into its cache. - CPU2 reads

x; at this point CPU2 sees the cache line state as Shared and readsx = 0(incorrect result). - CPU2’s cache changes the state of the cache line containing

xto Invalid and pops the corresponding instruction from the Invalidate Queue, but it is already too late.

One can still use smp_mb() to clear the contents of the Invalidate Queue, i.e., block until all loads issued before that point are visible to all CPUs.

Thoughts on Memory Barriers

In summary, we can see that the read‑write barrier mb() essentially flushes both the Store Buffer and the Invalidate Queue; the write barrier wmb() likely flushes only the Store Buffer, while the implementation of the read barrier rmb() is still not entirely clear.

Preprocessing

- Expand all macro definitions and conditional macros

- Insert the header files included by #include at the specified locations

- Remove comments, add file name and line number (for error reporting)

Compilation

The compilation process can be divided into six steps: lexical analysis, syntax analysis, semantic analysis, source code optimization, code generation, and target code optimization

The first four steps belong to the front end of the compiler, and the last two steps belong to the back end, based on the generation order of the intermediate language.

Specifically, lexical analysis splits the code into tokens, syntax analysis uses the tokens to produce an abstract syntax tree (AST), semantic analysis further processes the AST to check whether the program conforms to semantic rules, and source code optimization transforms the entire AST into intermediate code.

Assembly

The assembler translates a.s into machine language instructions and packages these instructions into a relocatable object file (i.e., a .o file).

Linking

Relocatable Object File

Its format and contents are as follows:

--------------------------------

| ELF Head | ELF Head, describing basic information of the object file

--------------------------------

| .text | Machine code

--------------------------------

| .rodata | Read-only data

--------------------------------

| .data | Initialized global and static variables

--------------------------------

| .bss | Uninitialized global and static variables (does not actually occupy space, only needs runtime initialization)

--------------------------------

| .symtab | Symbol table, stores all defined and referenced functions and global variables

--------------------------------

| .rel.text | Code relocation table, instructions that call external functions need relocation

--------------------------------

| .rel.data | Data relocation table, references to external global variables and external functions' global variables need relocation

--------------------------------

| .debug |

--------------------------------

| .line |

--------------------------------

| .strtab |

--------------------------------

|section header table|

--------------------------------

Static Linking

- The linker obtains the symbol tables of each object file and merges them into a single global symbol table.

- The linker obtains the lengths of each section of each object file, and calculates the length and position of each merged section.

- The start address of each section is defaulted to 0; at load time, fields are accessed via section base address + offset within the section.

-

Symbol Resolution

Each relocatable object file contains three types of symbols:

a. Symbols defined in the current module that cannot be referenced by other modules (static functions and global variables)

b. Symbols defined in the current module that can be referenced by other modules (functions and global variables without static)

c. Symbols referenced by the current module but defined in other modules (functions and global variables without static defined in other modules)

Mapping each symbol reference to its corresponding definition is symbol resolution, and the rules are as follows:

A strong symbol is a defined symbol with an initial value, while a weak symbol is declared but not defined.

a. There can be only one strong symbol.

b. If there is one strong symbol and multiple weak symbols, the strong symbol is chosen as the definition.

c. If there are multiple weak symbols and no strong symbol, any one weak symbol is chosen as the definition. -

Relocation

In the generated files above, the start address of each section defaults to 0; the linker needs to map symbol definitions to memory, and this mapping process is relocation.

a. The linker first merges the sections, creating a combined segment as the segment of the executable file.

b. Calculate the length and start address of each segment.

c. Based on each segment’s start address, assign runtime addresses (i.e., offsets within the segment) to the code/symbol references inside each segment. -

Advantages and Disadvantages of Static Linking

Advantages and Disadvantages of Static Linking

Disadvantages: waste of space, because each executable must contain a copy of all required object files; difficult to update, as any change to a library function requires recompiling and relinking.

Advantages: the executable contains everything it needs, resulting in fast execution speed.

Dynamic Linking

The basic idea of dynamic linking is to split the program into relatively independent modules and perform linking at runtime.

Suppose there are two programs, program1.o and program2.o, both using the same library lib.o. When program1 is run first, the system loads program1.o; upon detecting that program1.o uses lib.o (i.e., program1.o depends on lib.o), the system then loads lib.o. If program1.o and lib.o further depend on other object files, they are also loaded into memory. When program2 runs, program2.o is loaded, and it is found that program2.o depends on lib.o, but lib.o is already present in memory, so it is not reloaded; instead, the existing lib.o in memory is mapped into program2’s virtual address space, and linking (similar to static linking) produces an executable.

Runtime Relocation for Dynamic Linking

- Relocate the .so’s text and data to a memory segment.

- Relocate all references to the .so file within the executable.

An interesting detail here: when coding a linker in an ICS class, references to symbols in a dynamic library involve multiple pointer jumps on the first reference to locate the corresponding memory segment of the symbol and record its exact location; on subsequent references, the previously recorded location is used directly.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Dynamic Linking

Advantages: even if each program depends on the same library, there will not be multiple copies in memory as with static linking; instead, the programs share a single copy at runtime. Updating is easy: just replace the library file without relinking all programs.

Disadvantages: linking is deferred to runtime, incurring performance overhead.

Loading

The loader copies the executable’s code and data from disk into memory, then the PC jumps to the program’s first instruction or entry point.

Atomic Operations and Atomic Types

std::atomic

The atomic library defines the atomic type std::atomic<>, for example you can use std::atomic<int>.

std::atomic<> provides various atomic operations via member functions, such as std::atomic<>::load(), std::atomic<>::store(), std::atomic<>::fetch_and(), std:;atomic<>::fetch_add, etc.

CAS Operation

Implemented via atomic<>::compare_exchange_weak/strong(x, y). It means that if the atomic value equals x, it is set to y and returns true; otherwise x is updated with the atomic’s current value and returns false.

- weak has better performance but may return false even when it could return true.

- strong has worse performance but will always return true when it can.

C++ Memory Order

- seq_cst requires all atomic operations to appear to execute in program order; the strictest memory order.

- acquire ensures that all prior writes performed with release are visible to the current thread, and no statement after this one may be executed before this statement completes.

- release ensures that all writes before this statement have been performed and are visible to other threads.

- acq_rel ensures that before any read after this statement executes, all writes before this statement have been performed and are visible to other threads; and before any write after this statement executes, all reads before this statement have been performed.

- relaxed imposes no ordering constraints, the weakest memory order.

- consume

pthread (POSIX thread)

Mutexes and Spin Locks

When a thread wants to acquire a lock using a mutex, if the lock is currently held by another thread, the requesting thread will be blocked, a context switch will occur, and the thread will be placed in a waiting queue. The CPU can then be scheduled to do other work, and once the lock becomes available, the thread will resume execution.

When a thread wants to acquire a lock using a spin lock, if the lock cannot be obtained immediately, it will busy‑wait continuously until the lock is acquired.

In practice, mutexes are used when the expected wait time to acquire the lock is relatively long, while spin locks are used when the expected wait time is short.

Condition Variables

std::condition_variable

Functions used:

-

pthread_cond_init/destroy, similar to mutexes and spin locks

-

pthread_cond_wait

Function definition:

int pthread_cond_wait(pthread_cond_t *restrict cond, pthread_mutex_t *restrict mutex)

cond: pointer to the condition variable.

mutex: pointer to the mutex.

Before calling this function, the mutex must be locked. During the wait, the mutex is automatically released, and the calling thread is blocked until the condition variable is signaled and the mutex is re‑acquired. -

pthread_cond_signal/broadcast

Used to wake up threads waiting on the condition variable.signalwakes up one waiting thread (if multiple threads are waiting, only one is awakened);broadcastwakes up all waiting threads.

If no threads are waiting on the condition variable, the function has no effect.

Blocking Circular Queue

Copy some code from the internet:

#include

```<unistd.h>

#include <cstdlib>

#include <condition_variable>

#include <iostream>

#include <mutex>

#include <thread>

static const int kItemRepositorySize = 10; // Item buffer size.

static const int kItemsToProduce = 1000; // How many items we plan to produce.

struct ItemRepository {

int item_buffer[kItemRepositorySize]; // product buffer, used with read_position and write_position to model a circular queue.

size_t read_position; // position where consumer reads products.

size_t write_position; // position where producer writes products.

std::mutex mtx; // mutex protecting the product buffer

std::condition_variable repo_not_full; // condition variable indicating the product buffer is not full.

std::condition_variable repo_not_empty; // condition variable indicating the product buffer is not empty.

} gItemRepository; // global product repository variable, accessed by producer and consumer.

typedef struct ItemRepository ItemRepository;

void ProduceItem(ItemRepository *ir, int item)

{

std::unique_lock<std::mutex> lock(ir->mtx);

while(((ir->write_position + 1) % kItemRepositorySize)

== ir->read_position) { // item buffer is full, just wait here.

std::cout << "Producer is waiting for an empty slot...\n";

(ir->repo_not_full).wait(lock); // Producer waits for the condition that the product buffer is not full.

}

(ir->item_buffer)[ir->write_position] = item; // write product.

(ir->write_position)++; // advance write position.

if (ir->write_position == kItemRepositorySize) // If the write position reaches the end of the queue, reset to the initial position.

ir->write_position = 0;

(ir->repo_not_empty).notify_all(); // Notify consumers that the product buffer is not empty.

lock.unlock(); // unlock.

}

int ConsumeItem(ItemRepository *ir)

{

int data;

std::unique_lock<std::mutex> lock(ir->mtx);

// item buffer is empty, just wait here.

while(ir->write_position == ir->read_position) {

std::cout << "Consumer is waiting for items...\n";

(ir->repo_not_empty).wait(lock); // Consumer waits for the condition that the product buffer is not empty.

}

data = (ir->item_buffer)[ir->read_position]; // read a product

(ir->read_position)++; // advance read position

if (ir->read_position >= kItemRepositorySize) // If the read position moves to the end, reset it.

ir->read_position = 0;

(ir->repo_not_full).notify_all(); // Notify producers that the product buffer is not full.

lock.unlock(); // unlock.

return data; // return product.

}

void ProducerTask() // Producer task

{

for (int i = 1; i <= kItemsToProduce; ++i) {

// sleep(1);

std::cout << "Produce the " << i << "^th item..." << std::endl;

ProduceItem(&gItemRepository, i); // Loop to produce kItemsToProduce products.

}

}

void ConsumerTask() // Consumer task

{

static int cnt = 0;

while(1) {

sleep(1);

int item = ConsumeItem(&gItemRepository); // consume one product.

std::cout << "Consume the " << item << "^th item" << std::endl;

if (++cnt == kItemsToProduce) break; // If the number of consumed products equals kItemsToProduce, then exit.

}

}

void InitItemRepository(ItemRepository *ir)

{

ir->write_position = 0; // initialize product write position.

ir->read_position = 0; // initialize product read position.

}

int main()

{

InitItemRepository(&gItemRepository);

std::thread producer(ProducerTask); // create producer thread.

std::thread consumer(ConsumerTask); // create consumer thread.

}

The above code implements a single‑producer single‑consumer model; a multi‑producer multi‑consumer model only needs to add two counters to track how many items have been produced/consumed so far.

## Lock-Free Circular Queue

The kernel implements a lock‑free circular queue called **kfifo**.

Paste the code:

```c

/**

* __kfifo_put - puts some data into the FIFO, no locking version

* @fifo: the fifo to be used

* @buf: the data source

* @len: the length of the data

*

* Returns the number of bytes copied.

*/

static unsigned int __kfifo_put(struct __kfifo *fifo,

const unsigned char *buf, unsigned int len)

{

unsigned int i;

unsigned int l;

// calculate write space: queue size - write position + read position

l = __kfifo_len(fifo);

/*

* Ensure that we sample the fifo->out index -before-

* we start putting bytes into the kfifo.

* memory barrier (full barrier)

*/

smp_mb();

/* first put the data starting from fifo->in to buffer end */

/* write from the queue write position (mod queue size) to the end of the queue */

i = min(len, fifo->size - fifo->in);

memcpy(fifo->buffer + fifo->in, buf, i);

/* then put the rest (if any) at the beginning of the buffer */

/* write remaining data from the start of the queue */

memcpy(fifo->buffer, buf + i, len - i);

/*

* Ensure that we add the bytes to the kfifo -before-

* we update the fifo->in index.

* memory barrier (write barrier)

*/

smp_wmb();

fifo->in += len;

// monotonically increasing write position

return len;

}

/**

* __kfifo_get - gets some data from the FIFO, no locking version

* @fifo: the fifo to be used

* @buf: where to store data

* @len: the length of the data

*

* Returns the number of bytes copied.

*/

static unsigned int __kfifo_get(struct __kfifo *fifo,

unsigned char *buf, unsigned int len)

{

unsigned int i;

unsigned int l;

// calculate read space: write position - read position

l = __kfifo_len(fifo);

/*

* Ensure that we sample the fifo->in index -before-

* we start removing bytes from the kfifo.

* memory barrier (read barrier)

*/

smp_mb();

/* first get the data from fifo->out until the end of the buffer */

/* read from the queue read position (mod queue size) to the end of the buffer */

i = min(len, fifo->size - fifo->out);

memcpy(buf, fifo->buffer + fifo->out, i);

/* then get the rest (if any) from the beginning of the buffer */

/* read remaining data from the start of the buffer */

memcpy(buf + i, fifo->buffer, len - i);

/*

* Ensure that we remove the bytes from the kfifo -before-

* we update the fifo->out index.

* memory barrier (full barrier)

*/

smp_mb();

fifo->out += len;

// monotonically increasing read position

return len;

}

shared_ptr

shared_ptritself is not a thread‑safe STL, so concurrent reads and writes to the underlying memory region are unsafe.- Because assignment involves releasing the original memory, changing the pointer target, and other modifications, the process is not atomic; therefore concurrent assignment to a

shared_ptris not thread‑safe. - Concurrent copying of a

shared_ptronly reads and copies the data pointer and control block pointer, then increments the reference count, which is an atomic operation. Hence copying is thread‑safe.

#include <iostream>

#include <atomic>

class Counter {

public:

Counter() : count(0) {}

void add() { count++; } // increment

void sub() { count--; } // decrement

int get() const { return count; } // get current count

private:

std::atomic<int> count;

};

template <class T>

class Sp {

public:

Sp(); // default constructor

Sp(T *ptr); // parameterized constructor

Sp(const Sp &obj); // copy constructor

~Sp(); // destructor

Sp &operator=(const Sp &obj); // overload =

T *get(); // get the class pointed to by the shared pointer

int getcount(); // get the reference counter

private:

T *my_ptr; // object pointed to by the shared pointer

Counter* counter; // reference counter

void clear(); // cleanup function

};

template <class T>

Sp<T>::Sp()

{

// default constructor, parameter is null, constructs a reference counter

my_ptr = nullptr;

counter = new Counter;

counter->add();

}

template <class T>

Sp<T>::Sp(const Sp &obj)

{

// copy constructor, new shared pointer points to the object pointed by the old shared pointer

// make the pointed object also become the target's pointed object

my_ptr = obj.my_ptr;

// obtain the reference counter so that both shared pointers use the same counter

counter = obj.counter;

// increment this object's reference counter by 1

counter->add();

}

template <class T>

Sp<T> &Sp<T>::operator=(const Sp &obj)

{

// clean up the currently referenced object and reference counter

clear();

// point to the new object and obtain its reference counter

my_ptr = obj.my_ptr;

counter = obj.counter;

// increment reference counter by 1

counter->add();

// return self

return *this;

}

template <class T>

Sp<T>::Sp(T *ptr)

{

// create a shared pointer pointing to the target class, construct a new reference counter

my_ptr = ptr;

counter = new Counter;

counter->add();

}

template <class T>

Sp<T>::~Sp()

{

// destructor, calls cleanup function when going out of scope

clear();

}

template <class T>

void Sp<T>::clear()

{

// cleanup function, decrements the reference counter; if it becomes 0, cleans up the pointed object's memory

// decrement reference counter by 1

counter->sub();

// if reference counter becomes 0, clean up object

if (0 == counter->get()) {

if (my_ptr) {

delete my_ptr;

}

delete counter;

}

}

// number of shared pointers referencing the current object

template <class T>

int Sp<T>::getcount()

{

return counter->get();

}

template< typename T >

T * sp<T>::get()

{

return my_ptr;

}

LRU Replacement Algorithm Implementation

A LeetCode problem that requires O(1) lookup and O(1) cacheline replacement using the LRU method.

It can be implemented using a doubly linked list; STL list is quite convenient.

class LRUCache {

public:

LRUCache(int capacity) {

this->capacity = capacity;

}

int get(int key) {

auto pos = _lruHash.find(key);

if (pos != _lruHash.end()) {

//Cache hit, adjust counter and update the position of the node corresponding to the key

list<pair<int, int>>::iterator ptr = pos->second;

//Transfer node using std::list::splice

//void splice (iterator position, list& x, iterator i);

//Transfers elements from x into the container, inserting them at position.

//Transfer the i‑th node of x to the position

_lruCacheList.splice(_lruCacheList.begin(), ptr);

return pos->second->second;

}

return -1;

}

void put(int key, int value) {

auto pos = _lruHash.find(key);

if (pos != _lruHash.end()) {

//Update cache, update the position of the corresponding node

list<pair<int, int>>::iterator ptr = pos->second;

ptr->second = value; //update data

_lruCacheList.splice(_lruCacheList.begin(), ptr);

} else {

//Add new cache entry

if (capacity == _lruHash.size()) {

//Cache is full, replace by deleting the data at the tail

pair<int, int>& back = _lruCacheList.back();

_lruHash.erase(back.first);

_lruCacheList.pop_back();

}

_lruCacheList.push_front(make_pair(key, value));

_lruHash[key] = _lruCacheList.begin();

}

}

private:

unordered_map<int, list<pair<int, int>>::iterator> _lruHash; //Convenient for lookup

list<pair<int, int>> _lruCacheList; //Store data

size_t capacity;

};

/**

* Your LRUCache object will be instantiated and called as such:

* LRUCache* obj = new LRUCache(capacity);

* int param_1 = obj->get(key);

* obj->put(key, value);

*/

LRU replacement for page tables is similar.

Virtual Memory and Memory Allocation?

Excerpt from this article: 虚拟内存:解决物理内存问题的策略-CSDN博客

Physical Address

-

Memory utilization issues

The way each process uses memory can cause fragmentation. Whenmalloctries to allocate a very large block, there may be enough free physical memory overall, but no sufficiently large contiguous free region. Scattered fragments of memory are wasted. -

Read/write safety issues

Physical memory itself has no access restrictions; any address can be read or written. Modern operating systems need to enforce different access permissions for different pages, such as read‑only data. -

Inter‑process safety issues

Processes do not have independent address spaces. A process that executes erroneous instructions or malicious code can directly modify another process’s data, or even kernel address space data—something the OS wants to prevent. -

Memory read/write efficiency issues

When many processes run simultaneously and the total memory required exceeds the available physical memory, some programs must be temporarily swapped to disk, and new programs are loaded into RAM. The frequent swapping of large amounts of data makes memory usage very inefficient.

Virtual Memory

Memory Segmentation

- Memory segmentation

Virtual memory is divided into segments such as code, data, stack, and heap.

A. How physical memory maps to virtual memory under a segmentation scheme

Segmentation uses a segment selector and an offset within the segment.

Segment selector: stored in a segment register; it contains the segment number, flags, etc. The segment number indexes a segment table, which holds the base address, limit, and privilege level of each segment.

Offset: the physical address is generally segment base address + offset.

B. Problems

Fragmentation: Segmentation allocates on demand, so internal fragmentation does not occur, but external fragmentation can appear—multiple scattered free regions that are hard to reuse. One way to handle external fragmentation is swapping: each virtual segment is swapped to secondary storage (disk) one by one, which is inefficient. If a very large program is swapped, the whole system can become sluggish.

Memory Paging

Paging cuts the entire virtual and physical address spaces into fixed‑size blocks called pages. In Linux, each page is 4 KB.

Paging creates page tables and virtual page numbers.

Generally, the physical address is obtained by taking the virtual page number and the offset within the page, looking up the corresponding page table entry (the page table resides in memory) to get the physical page number, then adding the offset:

physical address = physical page number + page offset — this is mainly performed by the MMU (Memory Management Unit).

A. Problems

Fragmentation: Paging does not allocate on demand; it allocates whole pages (4 KB each). This leads to internal fragmentation because a page is often not completely filled.

Paging improves swapping efficiency

During swapping, only a few pages are moved between RAM and disk, rather than whole segments. This page‑level swapping reduces the overhead compared with segment‑level swapping.

Page tables consume memory (space overhead)

Because many processes can run concurrently, each needs its own page tables. In a 32‑bit environment, the virtual address space is 4 GB. With a 4 KB page size (2¹²), about 1 M (2²⁰) pages are needed. Each page‑table entry is 4 bytes, so mapping the entire 4 GB requires roughly 4 MB of memory for the page tables. Since each process has its own tables, memory consumption grows with the number of processes.

How to reduce page‑table memory usage

Use multi‑level page tables. Due to locality, most programs use far less than 4 GB, leaving many upper‑level entries unused. If a first‑level entry is not needed, its corresponding second‑level table is not created, saving a large amount of memory.

Benefits of Virtual Memory

-

Extends usable memory – Processes can use more memory than physically available. Because program execution follows the principle of locality, the CPU tends to access the same memory repeatedly. Infrequently used pages can be swapped out to disk (e.g., the swap area).

-

Isolation between processes – Each process has its own page table, making its virtual address space independent. Processes cannot access other processes’ page tables, preventing address conflicts.

-

Improved security – Page‑table entries contain not only the physical address but also bits for attributes such as read/write permissions and presence flags, allowing the OS to enforce stronger memory‑access protection.

-

Eliminates physical fragmentation – Virtual memory provides a contiguous address space, solving the low utilization problem caused by fragmented physical memory.

Memory Allocation

User‑space calls to malloc allocate heap memory, which actually performs a memory mapping. The relevant system calls are brk() and mmap(). Small allocations ( < 128 KB) use brk, while large allocations ( > 128 KB) use mmap.

brk

When small blocks are freed, they are not returned to the system immediately but kept in a cache that can be reused via brk. This reduces the frequency of page‑fault interrupts and improves memory‑access efficiency, but it can lead to fragmentation.

mmap

Large blocks are returned to the system directly when freed. Each mmap incurs a page‑fault interrupt; frequent large allocations cause many page faults, degrading performance.

I asked GPT to do it for me, and it’s the same way of writing.

Which one? The LRU one? I just went online, took a quick look and pasted a copy.

Is it possible that CRTP and virtual functions are not on the same level? Virtual functions correspond to dynamic dispatch.

Is there any problem with what I wrote?

Comparing the advantages and disadvantages of CRTP and virtual functions was the original question asked during a Jump interview.

Your sister points out the good points

Oh, when comparing, it should be limited to scenarios where both CRTP and virtual functions can be used, but we can indeed note that CRTP cannot perform dynamic dispatch.

The strengths of each side are written as the other’s weaknesses; just view it from the opposite perspective.

What are the three main forms of RTTI support in C++?

(It feels like this written‑test question is poorly written)

Common: typeid + dynamic_cast

There also seems to be a std::bad_cast

Memory Barriers and Compiler Barriers (C++)

Memory Barriers and Memory Order

Memory barriers are used to prevent the processor from reordering memory operations; they are tools at the hardware or compiler level.

Memory order refers to how multiple threads in a multithreaded program observe each other’s read and write operations; it is a high‑level abstraction provided by C++. It implicitly inserts memory barriers by specifying different memory order models. Programmers do not need to manipulate memory barriers directly, but instead control the order of memory accesses via atomic operations and memory order models.

Both aim to control memory operations, preventing unexpected errors caused by instruction reordering and cache coherence issues.

Memory Order

The discussion concerns how the execution order of instructions within a single thread affects multiple threads. Regardless of the memory order attached, an individual operation only affects its own thread, but several threads can establish indirect ordering relationships through variable synchronization, which are then influenced by their respective memory orders.

Memory Order Tags

c++ standard library defines six memory orders, ranging from relaxed to strict:

memory_order_relaxed: relaxed operation, only guarantees the atomicity of the atomic operation itselfmemory_order_consume: consume barrier, only affects writes to the currently loaded atomic variable and its dependent variables; otherwise same asmemory_order_acquire. Deprecated in C++20.memory_order_acquire: acquire barrier: all reads and writes in the current thread may not be reordered before this operation, making writes to the same atomic variable that occurred before a release in other threads visible to the current thread. In other words, it applies an “acquire” to loads of the relevant memory location, guaranteeing the latest value.memory_order_release: release barrier: all reads and writes in the current thread may not be reordered after this operation, making the writes of this operation visible to other threads that perform an acquire on the same atomic variable later. It applies a “release” to stores of the relevant memory location, ensuring the latest value is written.memory_order_acq_rel: acquire‑release barrier: reads and writes in the current thread cannot be reordered either after or before this operation.memory_order_seq_cst: sequentially consistent barrier: the order of reads and writes appears consistent to all threads.

Among them

- The default memory order tag for all atomic operations is

std::memory_order_seq_cst. - Two acquire barriers:

memory_order_consumeonly affects the current variable and variables that depend on it;memory_order_acquireaffects all variables before the current operation. - Two release barriers:

memory_order_acq_relis only effective for the current thread;memory_order_seq_cstis global.

Cooperative Combinations

Common cooperative combinations:

-

Relaxed order:

memory_order_relaxed

Only guarantees atomicity, allowing all instruction reordering. -

Release‑Acquire sequence:

memory_order_release+memory_order_acquire

Writes before the release are guaranteed to be visible; reads with acquire see the latest values. -

- Release‑Consume sequence:

memory_order_release+memory_order_consume

Slightly more relaxed than release‑acquire; only synchronizes the atomic variable itself and variables that depend on it.

- Release‑Consume sequence:

-

- Sequentially consistent order

memory_order_seq_cst

Disallows all reordering, visible to all threads.

- Sequentially consistent order

Example:

First define two variables

std::atomic<std::string *> ptr;

int data;

Release‑Acquire sequence

void producer() {

auto *p = new std::string("Hello");

data = 42;

// The compiler may not move the `data = 42` instruction after the store operation

// `memory_order_release` releases the result of the modification (write operation); other threads using `memory_order_acquire` can observe the memory write. This ensures the producer's modification is definitely written.

ptr.store(p, std::memory_order_release);

}

void consumer() {

std::string *p2;

// `memory_order_acquire` reads the latest value; values written before a `memory_order_release` in other threads are guaranteed to be readable. This ensures the consumer reads the value written by the producer.

while (!(p2 = ptr.load(std::memory_order_acquire)))

;

// Reaching this point indicates that `p2` is non‑null, i.e., the `data = 42` instruction has been executed (guaranteed by `memory_order_release`).

// Moreover, `data` must be 42 and `p2` must be "Hello" (guaranteed by `memory_order_acquire`).

assert(*p2 == "Hello");

assert(data == 42);

// No error will occur

}

Release‑Consume sequence

void producer() {

std::string* p = new std::string("Hello");

data = 42;

ptr.store(p, std::memory_order_release);

}

void consumer() {

std::string* p2;

while (!(p2 = ptr.load(std::memory_order_consume)))

;

assert(*p2 == "Hello"); // No error: *p2 carries a dependency from ptr

assert(data == 42); // May error: data does not carry a dependency from ptr

}

Memory Barriers

The C++ standard library provides the following interface

std::atomic_thread_fence: an explicit memory barrier. Used together with memory order tags, it divides threads into stages, where each stage must wait for other threads to complete specific operations before proceeding. It applies to all data, not just atomic variables.

The default memory order tag for all atomic operations is std::memory_order_seq_cst.

It can be considered that:

- 2.a write barrier combined with the write operation 2.b elevates 2.b to a release‑store

- 3.b read barrier combined with the read operation 3.a elevates 3.a to an acquire‑load

- The synchronization relationship is similar to the earlier memory order example, ensuring that 1 always occurs before 4

Example (comments translated):

std::atomic<bool> x,y;

void write_x_then_y() {

x.store(true, std::memory_order_relaxed); // 1

std::atomic_thread_fence(std::memory_order_release); // 2.a write barrier

y.store(true, std::memory_order_relaxed); // 2.b

}

void read_y_then_x() {

while(!y.load(std::memory_order_relaxed)); // 3.a

std::atomic_thread_fence(std::memory_order_acquire); // 3.b read barrier

assert(!x.load(std::memory_order_relaxed));// 4

}

It can be considered that:

- 2.a write barrier combined with the write operation 2.b elevates 2.b to a release‑store

- 3.b read barrier combined with the read operation 3.a elevates 3.a to an acquire‑load

- The synchronization relationship is similar to the earlier memory order example, ensuring that 1 always occurs before 4

Memory Barriers and Compiler Barriers

Compiler barriers only affect the compiler. They prevent the compiler from reordering instructions, ensuring that the generated assembly preserves the order specified in the source code, but they do not emit actual hardware instructions, so they do not affect CPU or memory access order. They cannot handle cache coherence or memory visibility issues arising from thread concurrency and are typically used on single‑core processors.

Memory barriers affect both the compiler and the CPU. They prevent the compiler from reordering operations and also emit hardware instructions that affect the CPU’s memory access order. They ensure data synchronization between threads and are commonly used on multi‑core processors.

Compiler Barriers

std::atomic_signal_fence: a compiler barrier that applies to all data. Used to prevent the compiler from reordering instructions in signal handlers or when interacting with hardware.volatilekeyword:- For a volatile variable, operations related to it must read/write to memory, not just read/write a cached register value.

- For multiple volatile variables, the access order between them will not be changed by the compiler.

A compiler barrier essentially tells the compiler that the values of these variables may change outside the program’s control and should not be assumed constant. It is commonly used in signal handling, hardware interaction, and embedded system interrupt routines.

// thread1

volatile bool tag = true;

volatile int x = 0;

while(tag);

assert(!x);

// thread2

x = 10;

tag = false;

On a single‑core processor, these two threads exhibit “pseudo‑concurrency”; volatile has two effects here:

- Each iteration reads the latest value of

tagfrom memory, preventing thread1 from looping forever. - The read/write order of

xandtagmatches the source code, i.e.,x = 10definitely occurs beforetag = false.

However, on a multi‑core processor with “true concurrency”, even though volatile forces the compiler to generate code that reads/writes from main memory, the actual execution order is still determined by the CPU. In this case, memory barriers are needed to enforce the required logic, ensuring memory operations occur in the specified order.