Connecting the Dots to the Future

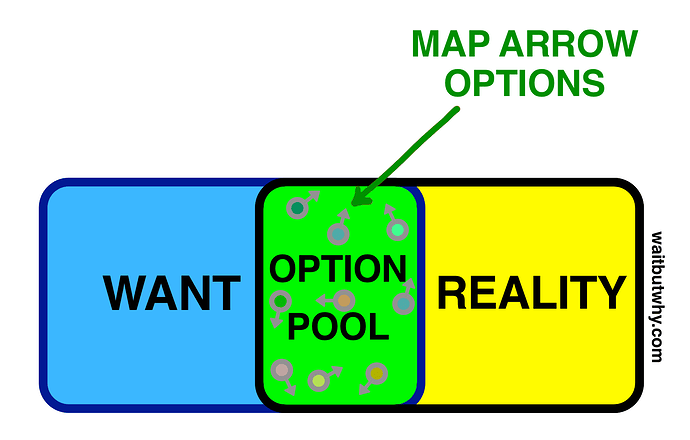

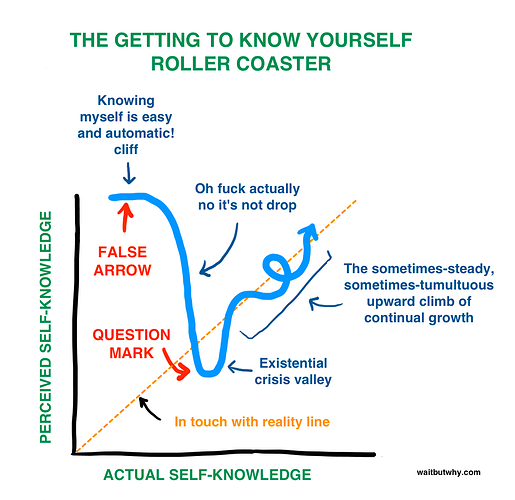

Now it’s time to pull out the career‑planning diagram I asked you to set aside at the start of the article — the one marked with an arrow or a question mark. If you had already drawn an arrow before you began examining it, then look at your new Option Pool. After some careful thought, does your current career plan still meet the criteria? If so, congratulations — you’re already ahead of most of us.

If not, that’s certainly bad news, but it’s also good news. Remember, turning a false arrow into a question mark is always a big step forward in life.

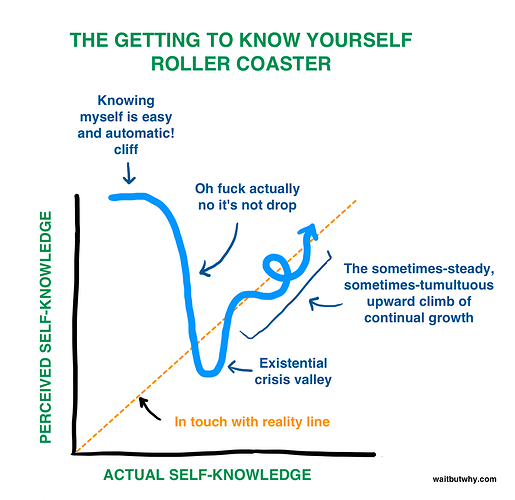

In fact, a new question mark means you’ve completed a crucial cliff‑jump on two roller‑coaster tracks: knowing yourself and understanding the world. It’s an important step in the right direction. Cross out the arrow and join the question‑mark camp.

Now the question‑mark camp faces a tough choice. You have to pick an arrow from the option pool.

It’s a hard choice — but it should be a lot easier than it feels. Here’s why:

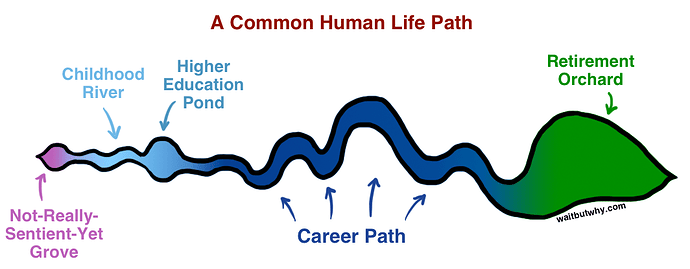

Past careers are a bit like a 40‑year tunnel. You chose the tunnel, and once you’re in, you can’t turn back. You work in that career for about 40 years until the tunnel spits you out into retirement.

In fact, a career may never truly be a 40‑year tunnel; it only looks that way. At best, the traditional career of the past was just a tunnel‑like trajectory.

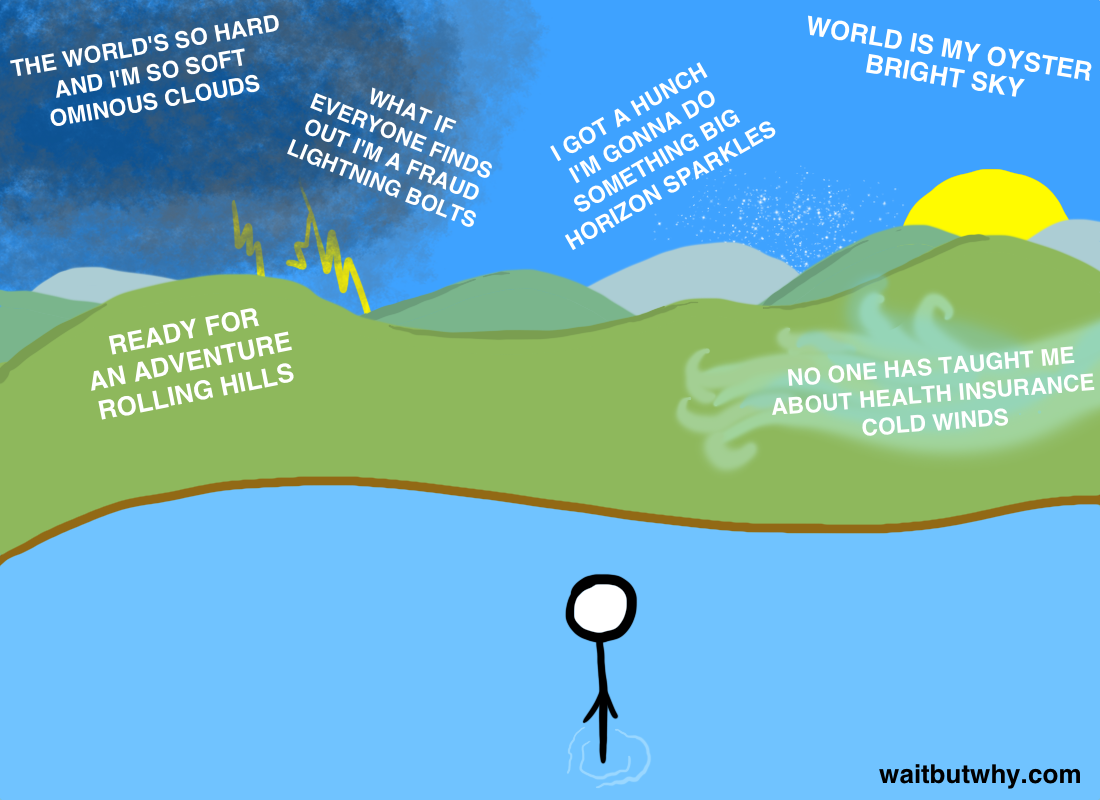

Today’s careers — especially the non‑traditional ones — are nothing like tunnels. Yet outdated conventional wisdom still leads many to view things that way, making an already difficult career‑path decision even trickier.

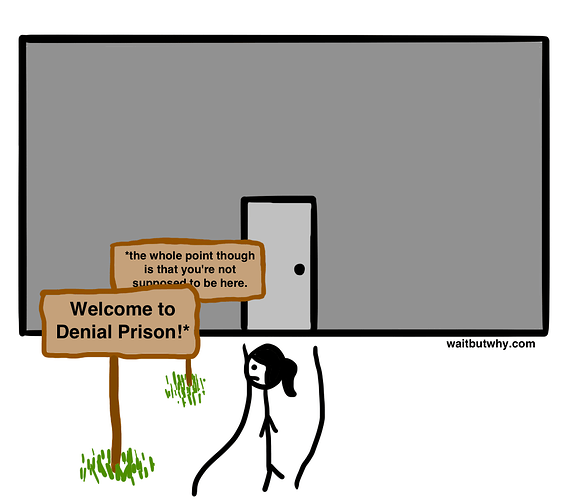

When you view a career as a tunnel, it triggers an identity crisis for anyone who isn’t sure who they are or what they want to become in the coming decades — a situation most rational people encounter. It reinforces the illusion that our work is our identity, making the question marks on the map look like an existential disaster.

When you see a career as a tunnel, the stakes of making the “right” choice feel so high that they amplify the pressure of choice‑aversion. For perfectionists, this feeling can be completely paralyzing.

When you see a career as a tunnel, even if your soul is calling, you lose the courage to switch careers. It makes career changes seem hugely risky and embarrassing, and suggests that those who do it are failures. It also makes many versatile, energetic middle‑agers feel they’re too old to boldly pivot or start a brand‑new path.

But the old narrative still tells many people that a career is a tunnel. Worse still — besides making us crave things we don’t truly want, denying deep‑seated desires, fearing things that aren’t dangerous, and believing inaccurate things about the world and our potential — the old narrative tells us the career is a tunnel, helping us scare ourselves unnecessarily.

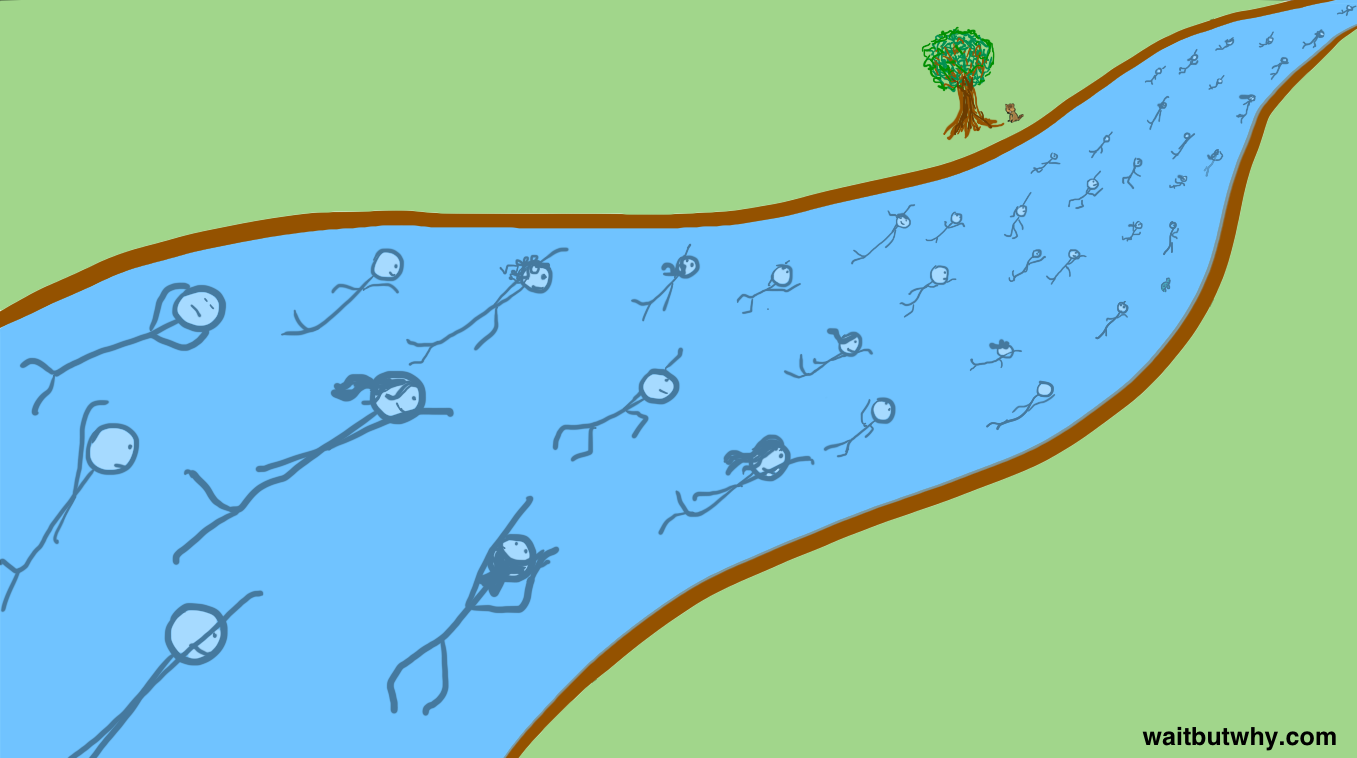

Today’s career landscape isn’t a series of tunnels; it’s a massive, extremely complex, rapidly changing scientific laboratory. People today can’t be reduced to their jobs — they are highly complex, fast‑evolving scientists. And today’s careers aren’t tunnels, boxes, or identity tags — they are a long series of scientific experiments.

Steve Jobs likened life to connecting the dots, pointing out that while it’s easy to look back and see how the dots linked to bring you to the present, it’s almost impossible to connect those dots ahead of time.

If you look at the biographies of the heroes you admire, you’ll see their paths look more like a series of connected dots than a straight, predictable tunnel. If you observe yourself and your friends, you’ll notice a similar trend — according to data, young people stay at a single job for an average of only 3 years (older workers stay a bit longer at each point, but not much — about 10.4 years on average).

Thus, viewing a career as a series of dots isn’t a psychological trick to help you decide — it’s an accurate description of reality. Viewing a career as a tunnel is not only unhelpful — it’s fantasy.

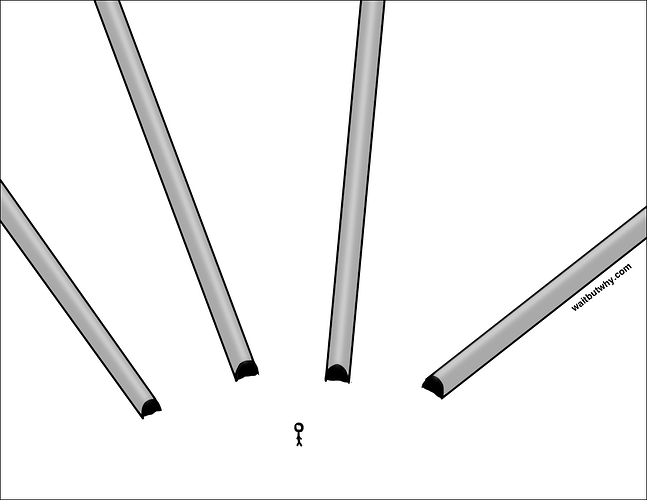

Likewise, you should focus on the next dot on your current path — because that’s the only dot you can actually figure out. You don’t need to worry about the fourth dot, because you can’t possibly do that — you’re not even qualified to consider that far ahead right now.

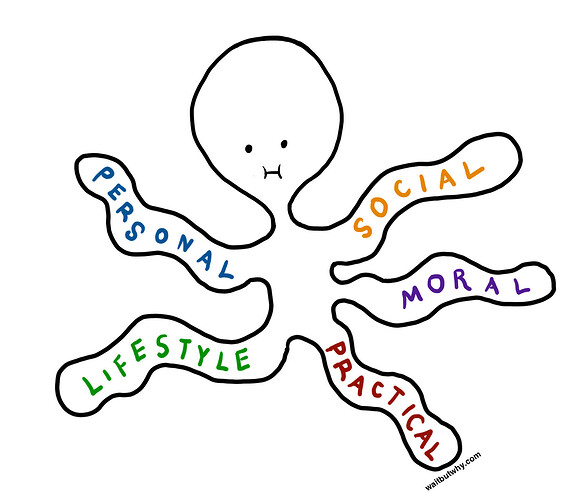

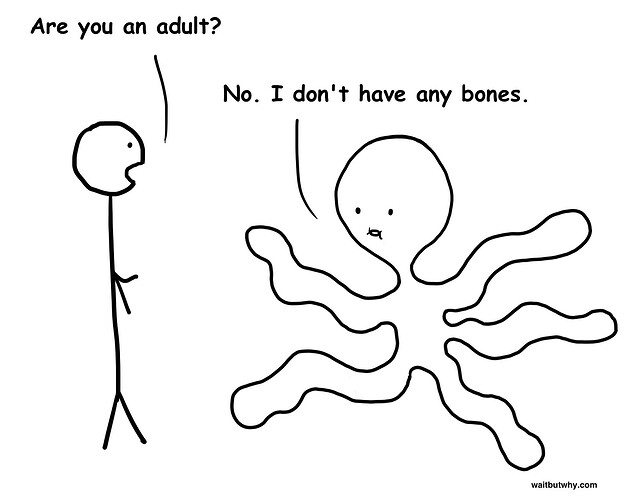

When the fourth dot arrives, you’ll learn things about yourself that you don’t know now. You’ll also be a different version of yourself; your “yearning octopus” will reflect those changes. You’ll have a better sense of what you’re good at, what career fields interest you, and the specific “rules of the game,” and you’ll become a better player. Of course, those fields and rules will also evolve.

The excellent site 80,000 Hours (which aims to help talented young people solve career‑choice problems) has gathered a lot of data supporting this: you’ll change, the world will change, you’ll only learn over time what you’re actually good at. Prominent psychologist Dan Gilbert also eloquently describes how terrible we are at predicting what will make us happy in the future.

Pretending you can now pinpoint what the 2nd, 4th, or 8th dot will look like is absurd. Future dots are problems the wiser‑future‑you will have to face, and that belongs to the future world. So let’s focus on the 1st dot.

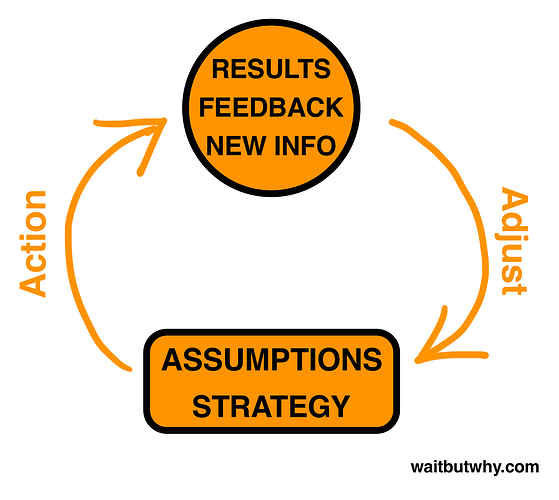

If we treat ourselves as scientists and society as a scientific laboratory, we should view the current revised “Wish‑Reality Venn diagram” as just a rough preliminary hypothesis. The 1st dot is your chance to test it.

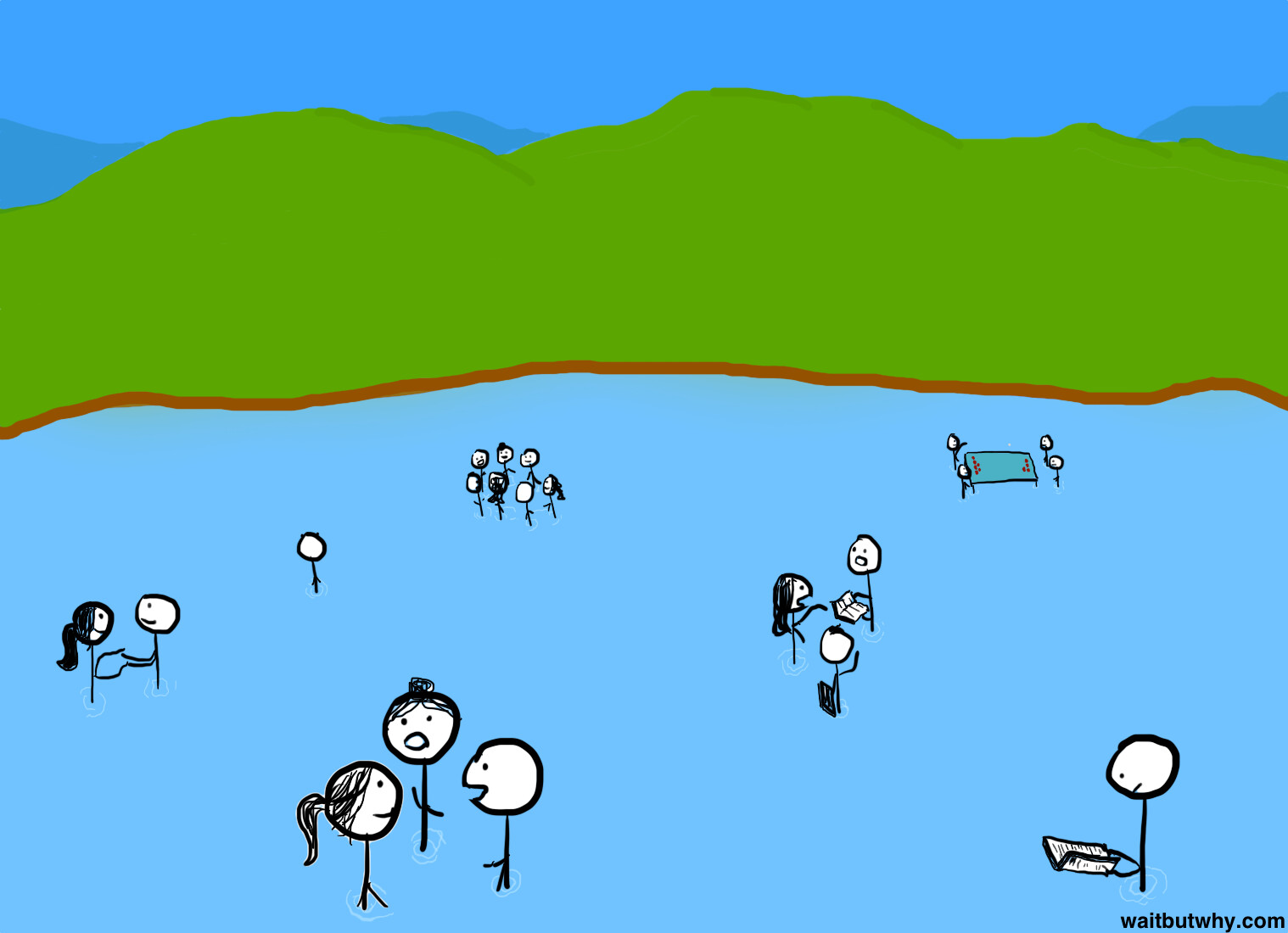

Hypothesis testing is intuitive in the dating world. If a friend keeps pondering what kind of person she wants to marry but never goes on dates, you’d say, “You can’t figure this out sitting on the couch — you have to start dating to learn what you want in a partner.” If that friend goes on a decent first date and then spends hours at home wondering whether the person is “the one,” you’d correct her: “One date can’t tell you that! You need multiple dates to accumulate the experience needed to make a decision.”

We’d all agree that this hypothetical friend is a bit crazy, lacking the basic understanding needed to find a happy relationship. So, when choosing a career, don’t be like her. The 1st dot is a low‑stakes situation — it’s just a first date.

That’s good news — because it dramatically reduces the pressure of drawing arrows on the map; it’s just an arrow pointing to the future 1st dot. The real cause of choice‑aversion is that you clearly see the many options the world now offers, yet you mistakenly treat those careers as a 40‑year tunnel of the past. That’s a lethal combination. Reframing your next major career decision as a low‑risk choice makes the many options exciting rather than stressful.

In theory all of this sounds great. But now we get to the hardest part.

Taking Action

You’ve reflected, weighed, forecasted, and considered repeatedly. You’ve picked a dot and drawn an arrow. Now you have to actually act.

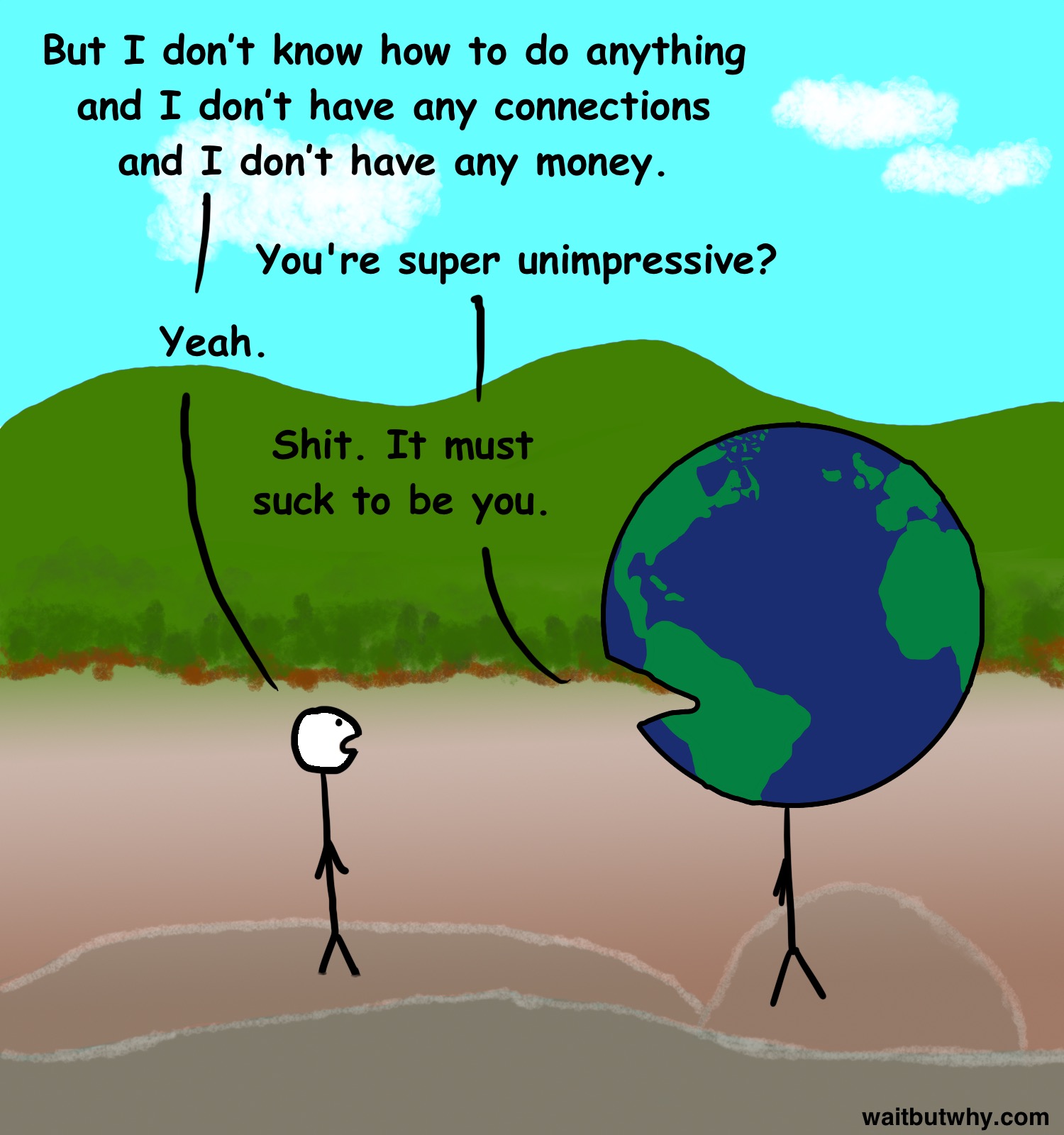

We’re especially bad at this. We’re timid people. We dislike hassle, and taking bold real‑life steps is a hassle. If we have any procrastination tendency, it shows up here.

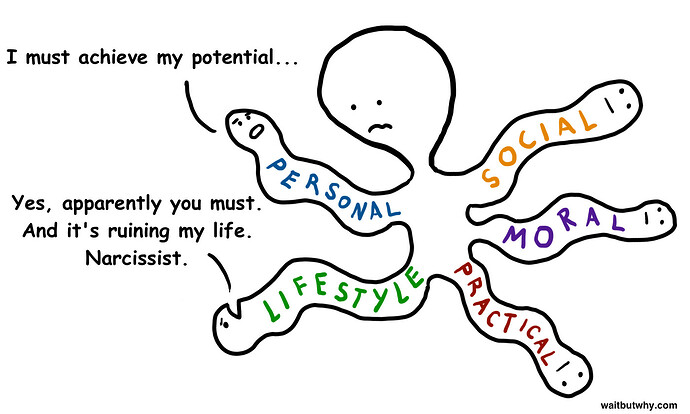

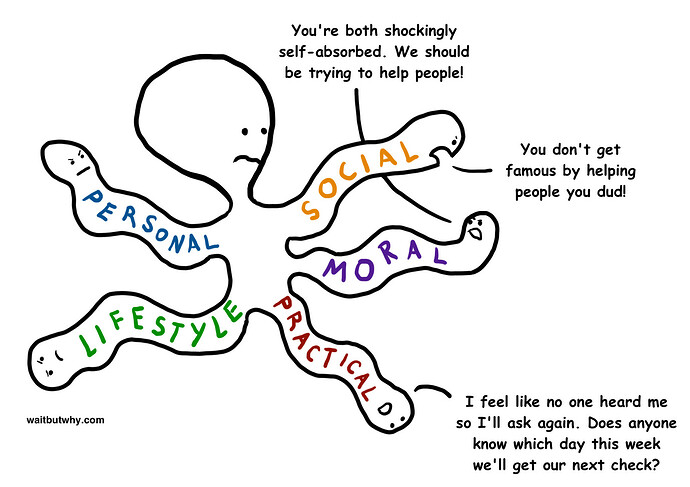

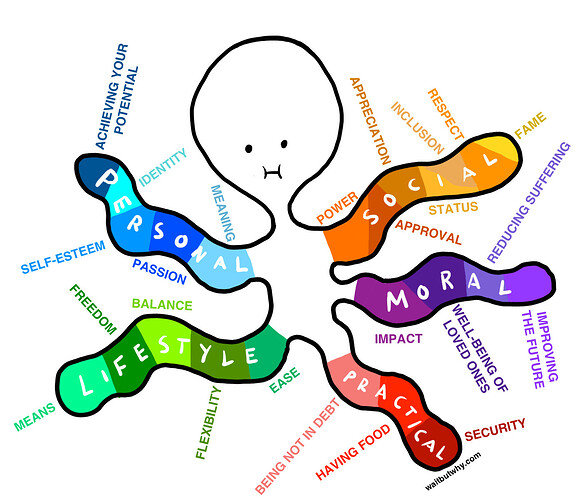

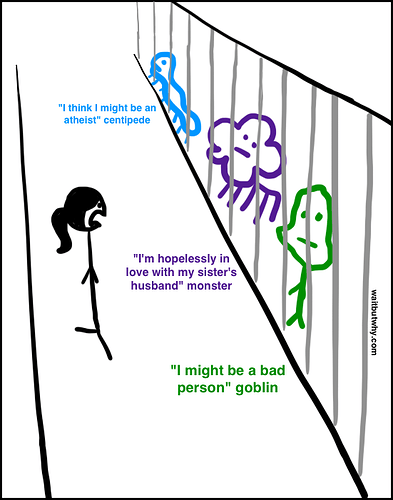

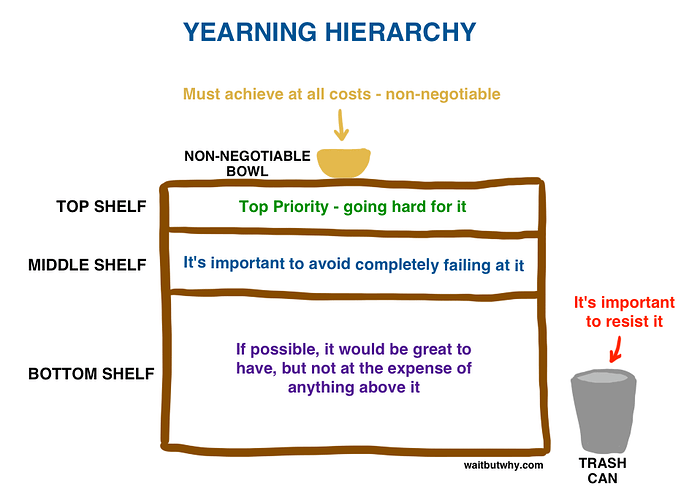

The “yearning octopus” can help us. As we discussed earlier, any behavior you exhibit simply shows the configuration of the octopus. If you decide on a life step but can’t execute it, it’s because the part of you that wants to act isn’t ranked high enough in the subconscious compared to the part that wants to stay idle. Your conscious mind may try to give the lazy part a low score, but your yearning fights back. You’re like a CEO who can’t control employees.

To solve this, think like a kindergarten teacher. In your class there’s a group of 5‑year‑olds rebelling against your wishes. What do you do?

Go talk to those troublesome 5‑year‑olds. They’re annoying, rebellious little creatures, but they can be reasoned with. Explain why you’ve placed them lower in the octopus hierarchy. Share the insights you gained from the “real‑frame reflection.” Remind them how dot‑connecting works and how easy the 1st dot is. You’re the teacher — figure out how to handle them.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized that the internal struggle of being the kindergarten teacher occupies about 97 % of life. The world is simple — you are complex. If you keep failing to follow through on life plans and commitments, you’ve identified a new top priority — become a better kindergarten teacher. Until you do, your life will be run by a bunch of primitive, anxious 5‑year‑olds, and you’ll feel the octopus’s constant complaining. The burden of constantly reinventing your life map never feels easy — but insecurity and difficulty are the feeling of steering your own ship. When we feel too good, we risk overconfidence, intellectual smugness, and rigidity. It’s precisely when we think we’ve fully mastered life that we lose our way.

Throughout your life, your good and bad decisions will together shape your unique road. In this blog I often write about how irrational our fears are and how severely they block us. Perhaps we should also embrace the fear of regret at life’s end.

I’ve been lucky never to face a dying‑bed scenario, but it seems the end of life lets people look at things with clear eyes. Facing death appears to melt away the “false” voices that aren’t yours, leaving a small, honest self to reflect. I think the regrets at life’s end may simply be the thoughts of your authentic self — about the parts of a life you never realized, the parts other people pushed into your subconscious.

My own psychology seems to support this — looking back over my path, the biggest mistakes that bother me are the ones where other people hijacked my mind, silencing my insecure, quiet true self — mistakes I knew deep down were wrong at the time. My goal for the future isn’t to avoid mistakes, but to make sure the mistakes I make belong to me.

That’s why this post involved such painful, rigorous analysis. I consider it one of the few life topics worth spending time on. The other strong voices trying to live for you will never stop — you owe an explanation to that small, uneasy character at the center of your consciousness.

Help Analyze Your Situation

Some worksheets to record: your octopus, your priority shelf, some path distances, your career‑dot map.

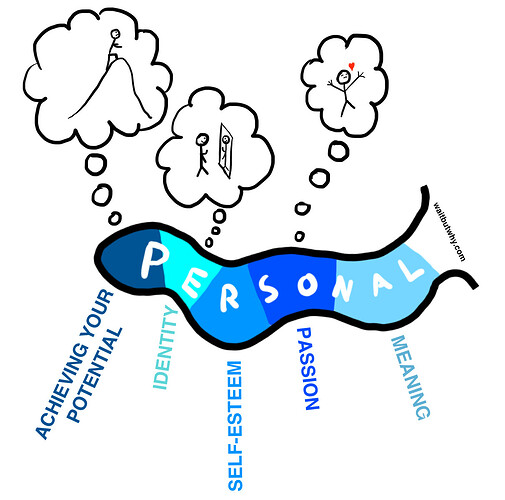

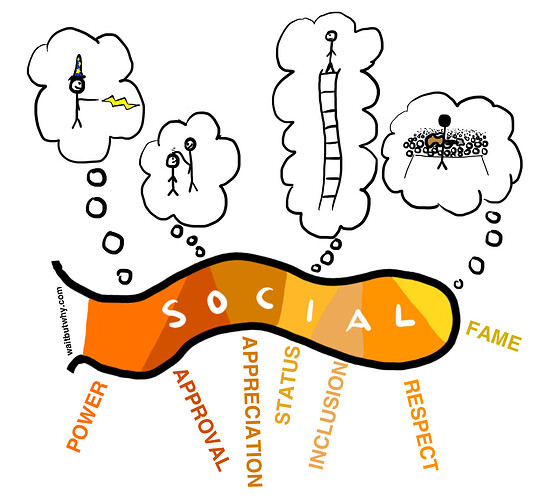

Your octopus.

Your priority shelf.

Some path distances.

Your career dot map.

For those who want to dig deeper: Alicia (WBW manager, responsible for many things) prepared a more detailed set of exercise sheets.

a more involved group of worksheets.

Further Exploration

The 80,000 Hours website — dedicated to helping talented young people make major career choices — is an excellent resource. The site is run by very smart, thoughtful, forward‑looking people and can be digested via videos, books or the website itself.

For years I’ve read Seth Godin’s blog Seth Godin’s blog. Seth shares short snippets each morning (I receive them by email). Many of his suggestions apply to career choices. For example this post (I adapted it into a comic for this article).

Eric Barker’s blog Eric Barker’s blog is full of practical data that help with career decisions, such as this article about what makes a career meaningful, or this one about the importance of mentors.

More deep human‑focused Wait But Why pieces:

Marriage decision: everything forever or never again

The Marriage Decision: Everything Forever or Nothing Ever Again

Why procrastinators procrastinate

Why Procrastinators Procrastinate

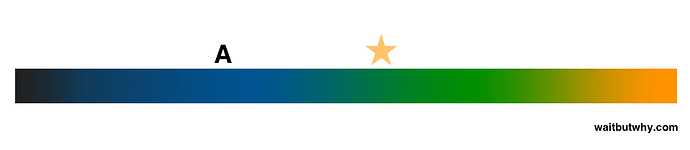

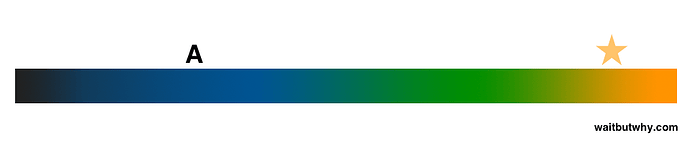

The spectrum’s left side consists of people who fear jumping. They are “concrete feet,” and their trap is staying too long on the wrong thing. The right side consists of people who love jumping — they are “light‑footed” and their trap is the opposite: they are quick abandoners [11]. (You should especially watch out for concrete feet — psychologists note that at the end of life people most often regret living out of inertia. A common regret is “If only I’d quit earlier” (Top Career Regrets), and the most common advice for seniors is “Don’t stay in a job you don’t like”* (Most Important Life Lesson).)*

[11]: Of course, this spectrum is also highly relevant in interpersonal relationships.An article about becoming smarter

And a post about getting wiser

There are also some less self‑reflective “Wait, but why” articles:

And a few less self-reflect-y Wait But Why posts on:

Awkward social interactions

Awkward social interactions

The history of everything

The history of everything

Colonizing Mars

Colonizing Mars