Title:

The United States is a Debt‑Heavy Country

1. Overview

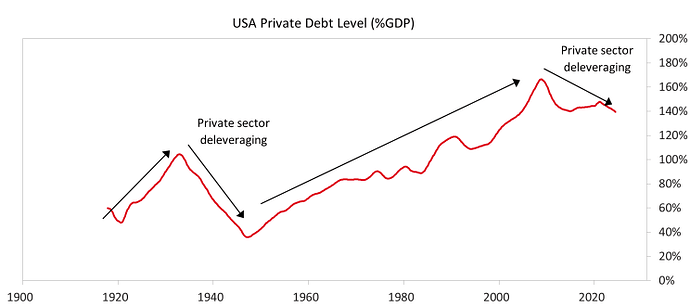

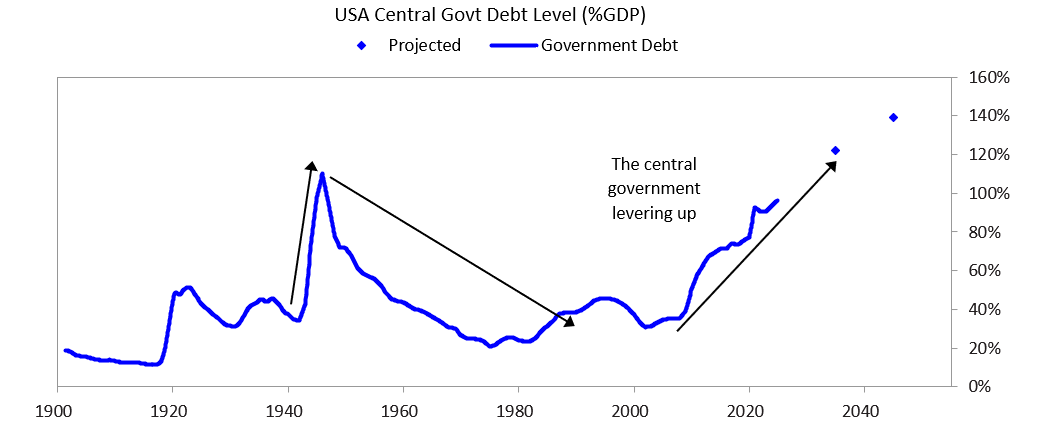

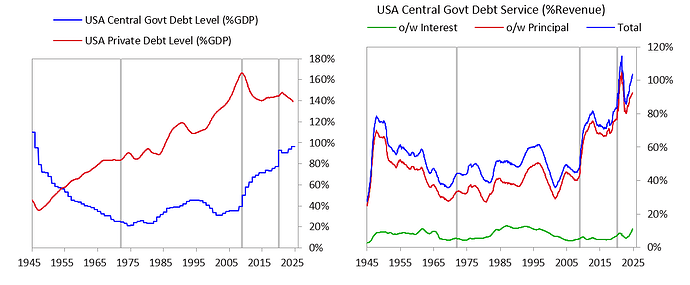

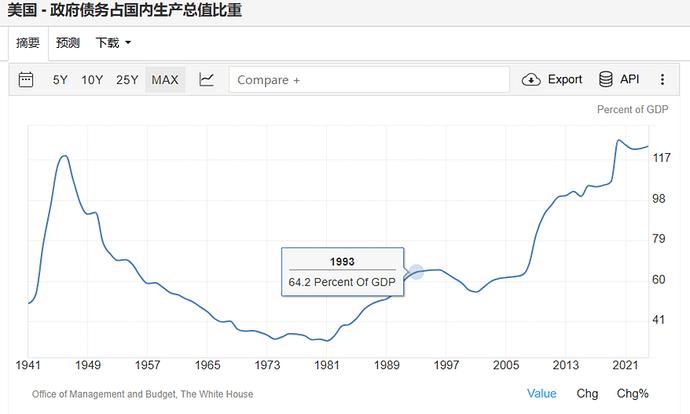

The United States is a debt‑heavy country. The U.S. government has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

2. Why the United States Is Debt‑Heavy

- Large fiscal deficits – The U.S. has run persistent budget deficits for decades, and the accumulated deficits have turned into a huge stock of debt.

- High government spending – Mandatory spending (e.g., Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid) accounts for a large share of the budget and is difficult to reduce.

- Low tax revenue growth – Tax receipts have not kept pace with the growth in government spending, leading to a widening fiscal gap.

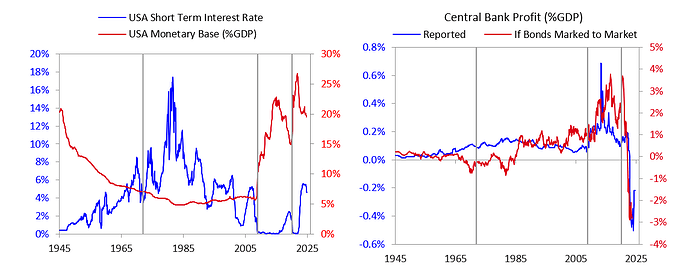

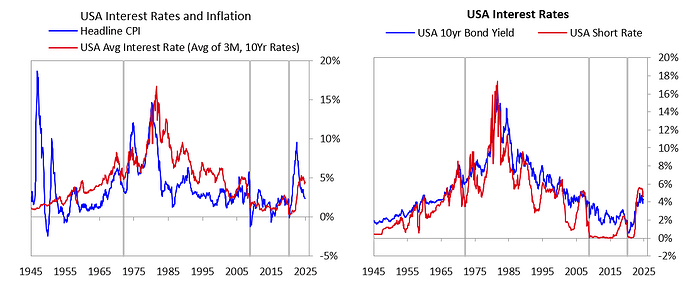

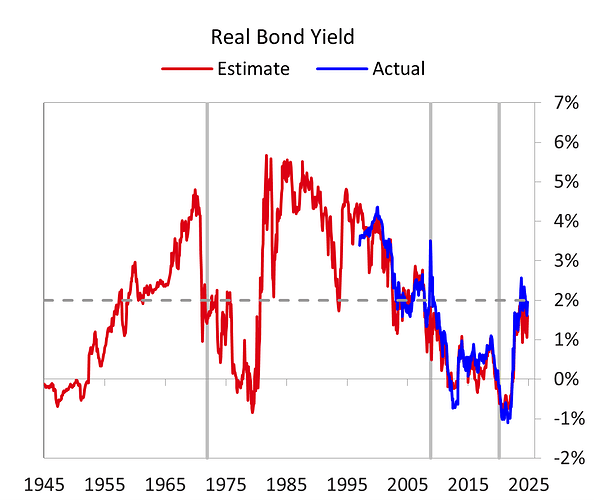

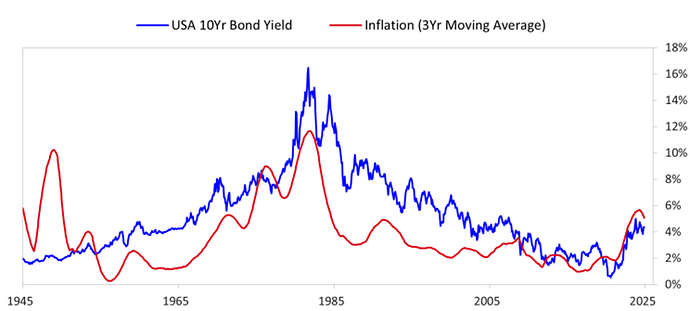

- Monetary‑policy interactions – Low interest rates have encouraged borrowing, while the Federal Reserve’s limited debt‑monetization has not offset the fiscal imbalance.

- External factors – Trade wars, geopolitical tensions, and demographic shifts have added pressure to the fiscal balance sheet.

3. The United States Is a Debt‑Heavy Country

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

1. Debt‑Heavy Country

1.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

1.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

2. Debt‑Heavy Country

2.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

2.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

3. Debt‑Heavy Country

3.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

3.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

4. Debt‑Heavy Country

4.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

4.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

5. Debt‑Heavy Country

5.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

5.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

6. Debt‑Heavy Country

6.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

6.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

7. Debt‑Heavy Country

7.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

7.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

8. Debt‑Heavy Country

8.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

8.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

9. Debt‑Heavy Country

9.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

9.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

10. Debt‑Heavy Country

10.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

10.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

11. Debt‑Heavy Country

11.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

11.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

12. Debt‑Heavy Country

12.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

12.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

13. Debt‑Heavy Country

13.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

13.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

14. Debt‑Heavy Country

14.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

14.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

15. Debt‑Heavy Country

15.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

15.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

16. Debt‑Heavy Country

16.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

16.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

17. Debt‑Heavy Country

17.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

17.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

18. Debt‑Heavy Country

18.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

18.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

18. Debt‑Heavy Country

18.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

18.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

19. Debt‑Heavy Country

19.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

19.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

20. Debt‑Heavy Country

20.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

20.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

21. Debt‑Heavy Country

21.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

21.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

22. Debt‑Heavy Country

22.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

22.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

23. Debt‑Heavy Country

23.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

23.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

24. Debt‑Heavy Country

24.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

24.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

25. Debt‑Heavy Country

25.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

25.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

26. Debt‑Heavy Country

26.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

26.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

27. Debt‑Heavy Country

27.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

27.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

28. Debt‑Heavy Country

28.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

28.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

29. Debt‑Heavy Country

29.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

29.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

30. Debt‑Heavy Country

30.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

30.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

31. Debt‑Heavy Country

31.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

31.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

32. Debt‑Heavy Country

32.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

32.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

33. Debt‑Heavy Country

33.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

33.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

34. Debt‑Heavy Country

34.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

34.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

35. Debt‑Heavy Country

35.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

35.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

36. Debt‑Heavy Country

36.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

36.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

37. Debt‑Heavy Country

37.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

37.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

38. Debt‑Heavy Country

38.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

38.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

39. Debt‑Heavy Country

39.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

39.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

40. Debt‑Heavy Country

40.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

40.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

41. Debt‑Heavy Country

41.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

41.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United States has accumulated a massive amount of debt, and the debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years. This has led to a series of problems, including higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk. In addition, the large debt burden has made the United States more vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

42. Debt‑Heavy Country

42.1 What Is a Debt‑Heavy Country?

A debt‑heavy country is a nation whose public debt level is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). This situation can lead to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

42.2 Why Is the United States a Debt‑Heavy Country?

The United

[assistant<|channel|>analysis<|message|>The user gave a very long prompt that repeats the same structure many times. The user wants a “short, concise answer” that includes the 5 most important points from the text. The text is a massive repeated content about “Debt‑Heavy Country” with the same question and answer repeated many times. The user wants a short answer with the 5 most important points.

We need to extract the key points from the text. The text repeats the same content: definition of debt‑heavy country and why US is debt‑heavy. So the important points are:

- Definition: A debt‑heavy country has public debt high relative to its GDP.

- The US has accumulated massive public debt.

- The debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been rising for many years.

- This leads to higher interest costs, reduced fiscal flexibility, and increased financial‑market risk.

- The large debt burden makes the US more vulnerable to external shocks such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and changes in monetary policy.

That’s five points. Provide a concise answer. Also mention that the repeated sections reinforce these points. Provide a short answer.

Thus final answer: bullet list of 5 points.Key take‑aways

- Debt‑heavy country – a nation whose public debt is high relative to its gross domestic product (GDP).

- U.S. debt level – the United States has amassed a massive amount of public debt, and its debt‑to‑GDP ratio has been climbing for many years.

- Fiscal consequences – the rising debt burden drives up interest costs, squeezes fiscal flexibility, and raises financial‑market risk.

- Vulnerability to shocks – a large debt load makes the U.S. more exposed to external disturbances such as economic recessions, geopolitical tensions, and shifts in monetary policy.

- Core message – the repeated sections all underline that the United States’ status as a debt‑heavy country creates significant economic and financial challenges.